|

|

|

|

| time on video |

elapsed time (ms) |

comments |

| 17:57:43.062968 |

start of video |

|

|

43.066160 |

0 |

stepped leader appears top right of center |

|

43.075316 |

9 |

1st return stroke |

|

43.091270 |

25 |

branch visible in picture (from another

stroke outside the frame?) |

|

43.119850 |

54 |

dart leader |

|

43.121652 |

56 |

2nd return stroke (more distant strike

point) |

|

43.149816 |

84 |

3rd return stroke (at more distant strike

point) |

|

43.171735 |

106 |

new stepped leader |

|

43.187551 |

121 |

4th return stroke (at original location) |

|

43.206002 |

140 |

dart leader |

|

43.206696 |

140 |

5th return stroke with continuing current

at more distant location again |

|

43.522490 |

end of continuing current |

| peak current |

10 kA |

| peak current

derivative |

100 kA/μs |

| velocity |

1 x 108 m/s |

|

|

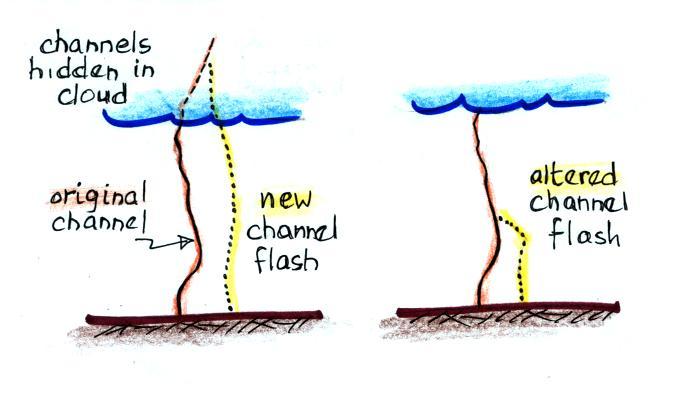

| Tracing of a still photograph

(20 second exposure) of positive upward streamers that

developed off the tops of 4 transmission towers in Rapid

City, South Dakota. See T.A. Warner, "Observations of simultaneous upward lightning leaders from multiple tall structures," Atmos. Res., 117, 45-54, 2012. |

Tracing of a superposition (time

integration) of images captured with a high-speed video

camera (7207 images/sec). The high speed camera has

greater light sensitivity than the still camera. |