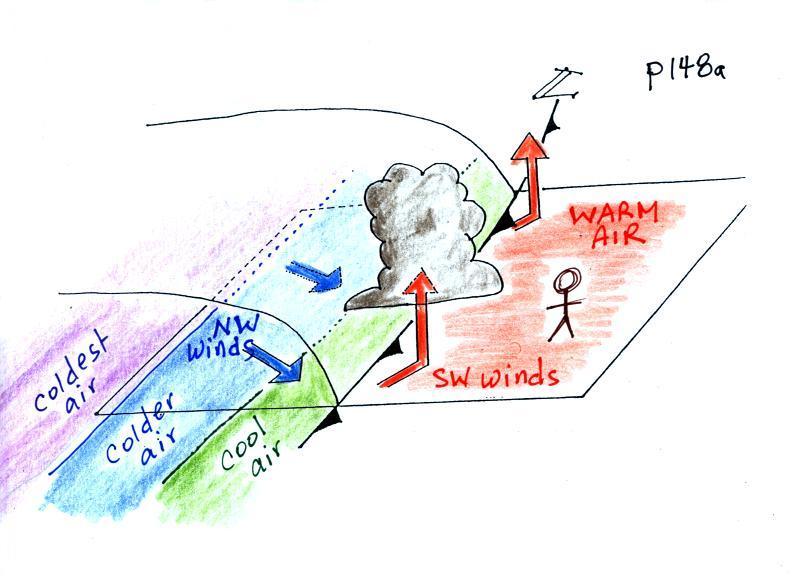

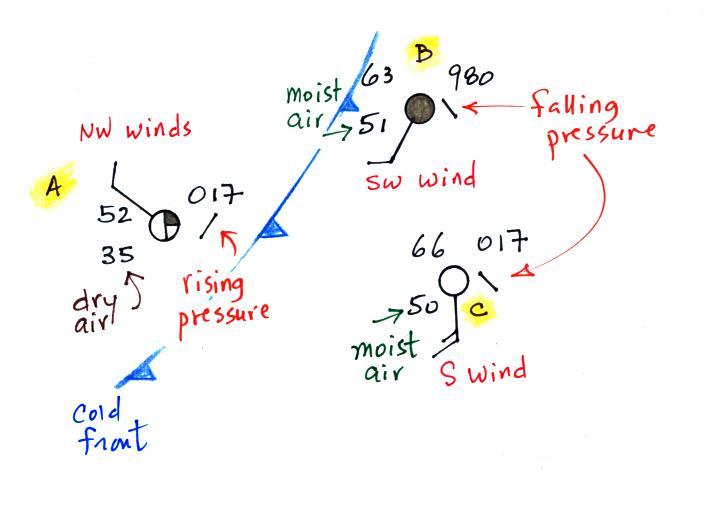

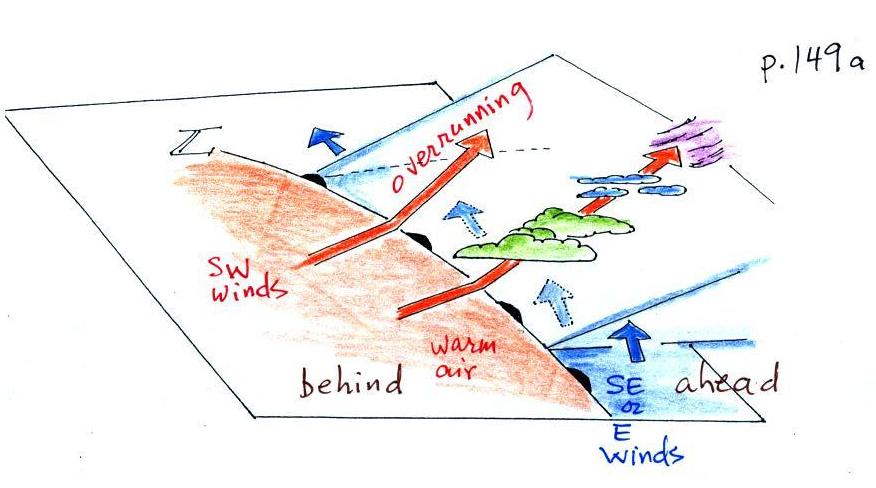

The person in the

figure is positioned ahead of an approaching

cold front. Time wise, it might be the day before

the front actually passes through. There

are 3 fairly important features to notice in this

picture.

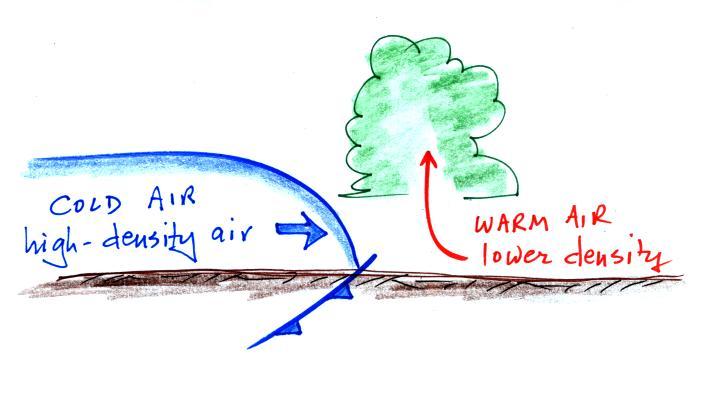

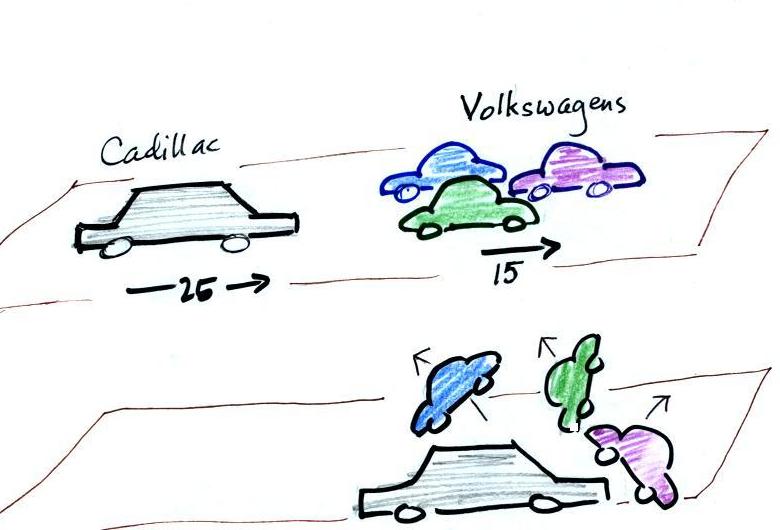

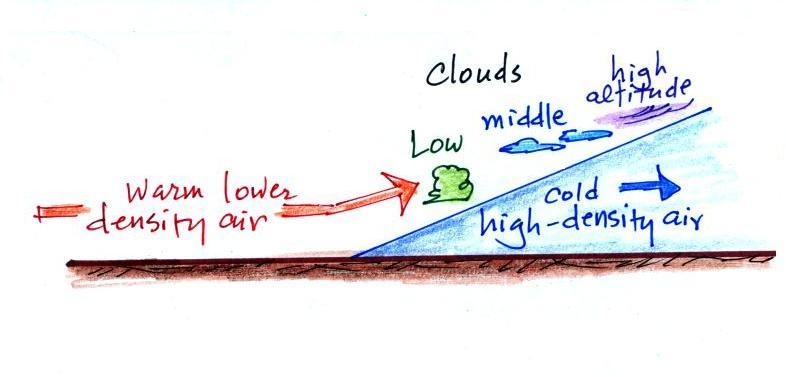

1. The

front edge of the approaching air mass has a

blunt, rounded shape. A vertical slice

through a cold front is shown below at left.

Here are the kinds

of weather changes that usually precede and follow

passage of a warm front.

Weather

Variable

|

Behind

(after)

|

Passing

|

Ahead

(before)

|

Temperature

|

warmer

|

|

cool

|

Dew point

|

may be moister

|

|

drier

|

Winds

|

SW, S, SE

|

|

from the East or SE,

maybe even the S

|

Clouds,

Weather

|

clearing

|

|

wide

variety of clouds that may precede arrival of the front

by a day or two

clouds may produce a wide variety of types of

precipitation also

(snow, sleet, freezing rain, and rain)

|

Pressure

|

rising

|

minimum

|

falling

|

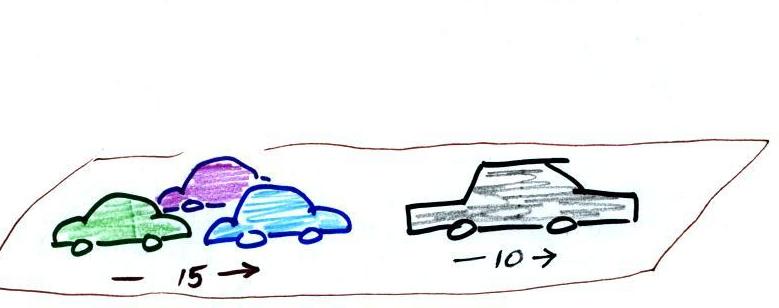

Probably the key difference

between warm and cold fronts (other than a cold-to-warm

rather than a warm-to-cold change) is the wide variety of

clouds that a warm front cause to form cover a much larger

area out ahead of the front. That's why it's

highlighted above. This happens because the warm air

rises more gradually and moves out over a wider area ahead

of the warm front as it rises.

Clouds associated with a cold front are

usually found in a fairly narrow band along the

front. The warm air is pushed up abruptly. All

of the lifting is confined to a fairly narrow band.

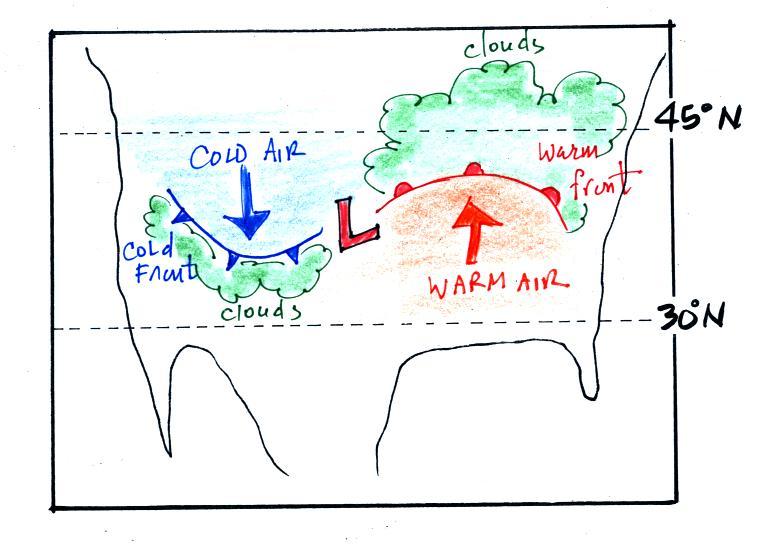

Locating

a warm front on a weather map

We need to finish our study of surface weather

maps by trying to located a warm front.

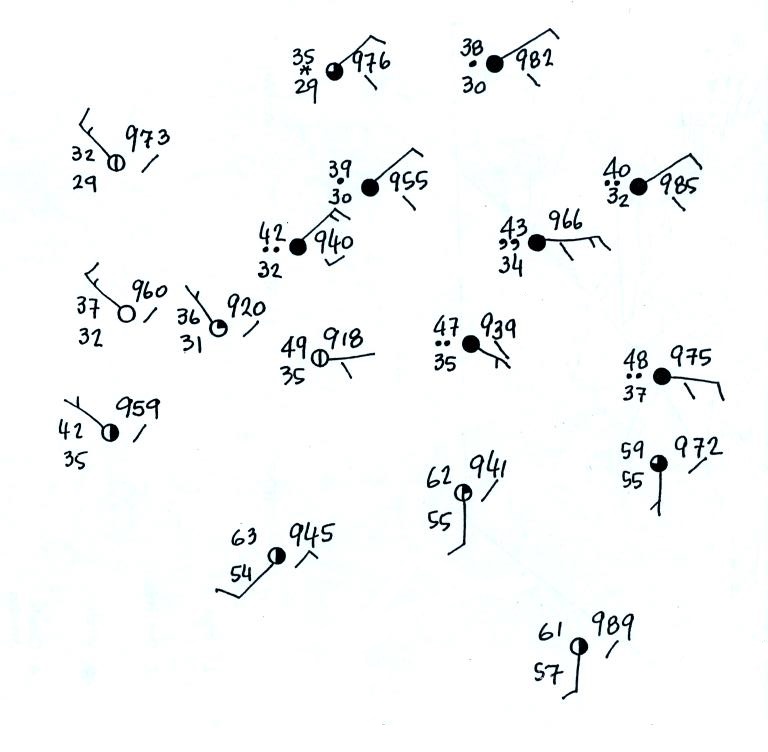

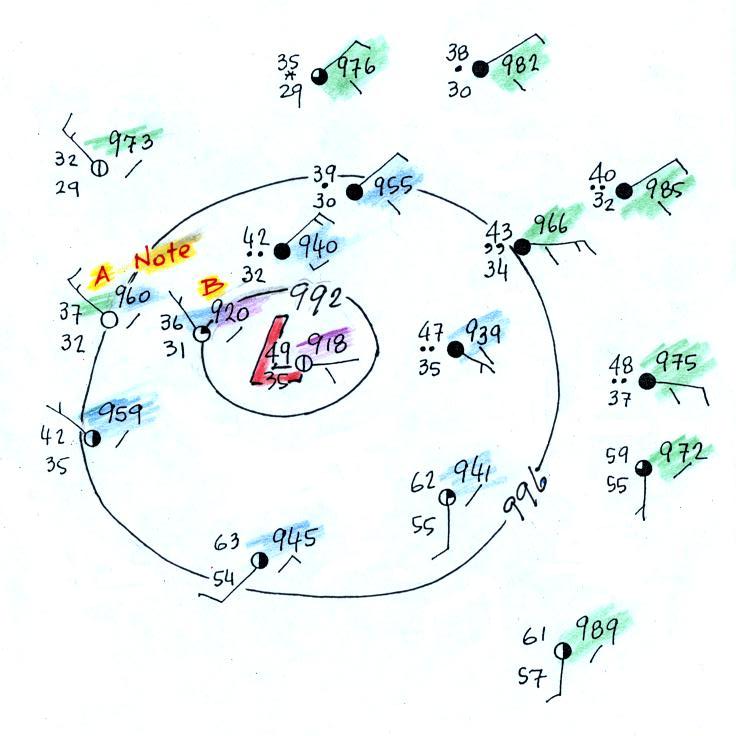

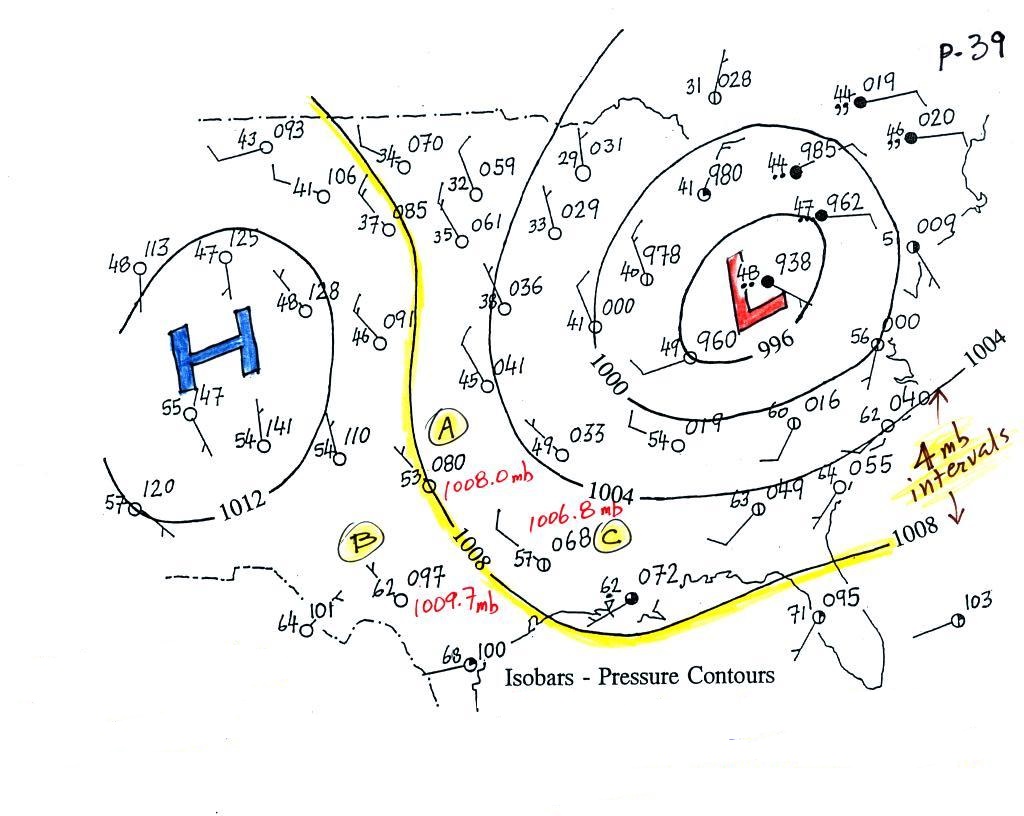

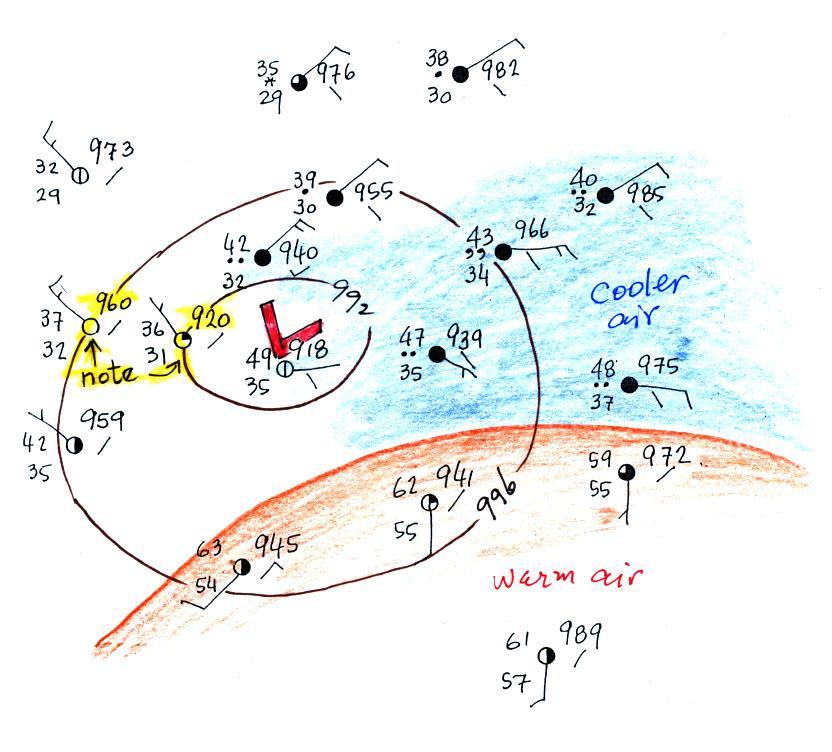

This is the map we will be working with

(see p. 149b in the ClassNotes). It's worth pausing

and noting that you really can't make any sense out of this

jumble of weather data at this point.

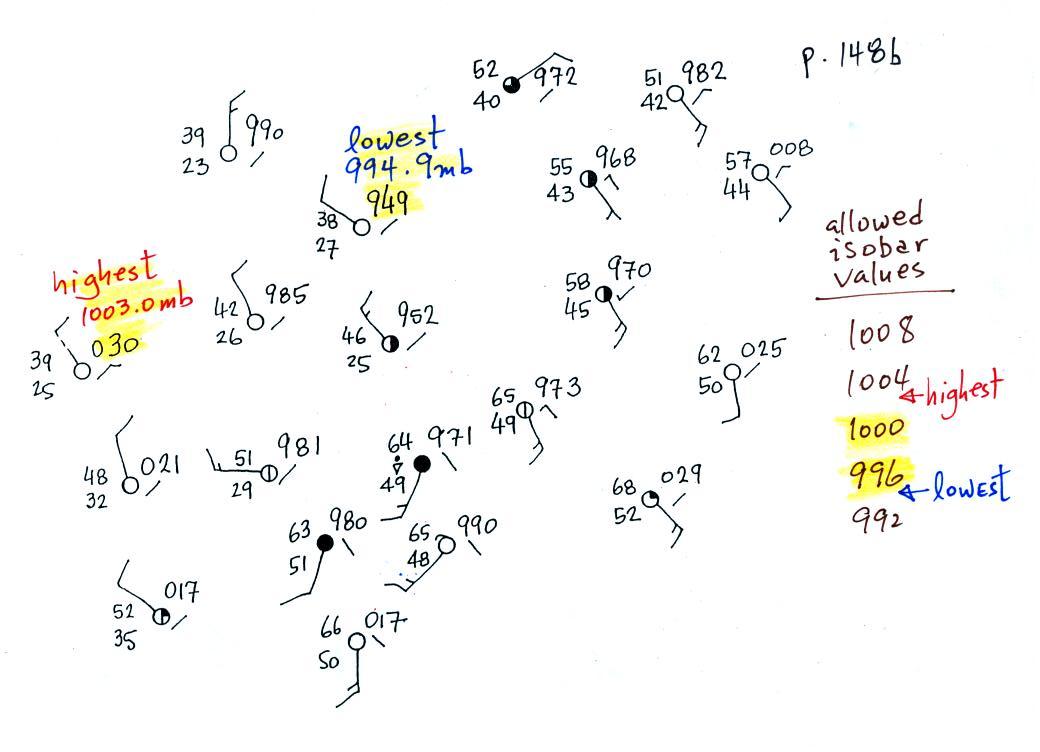

Step #1

We'll start by drawing some isobars to map out the

pressure pattern. A partial list of allowed isobars is

shown at the right side of the map above (increments of 4 mb

starting at 1000 mb).

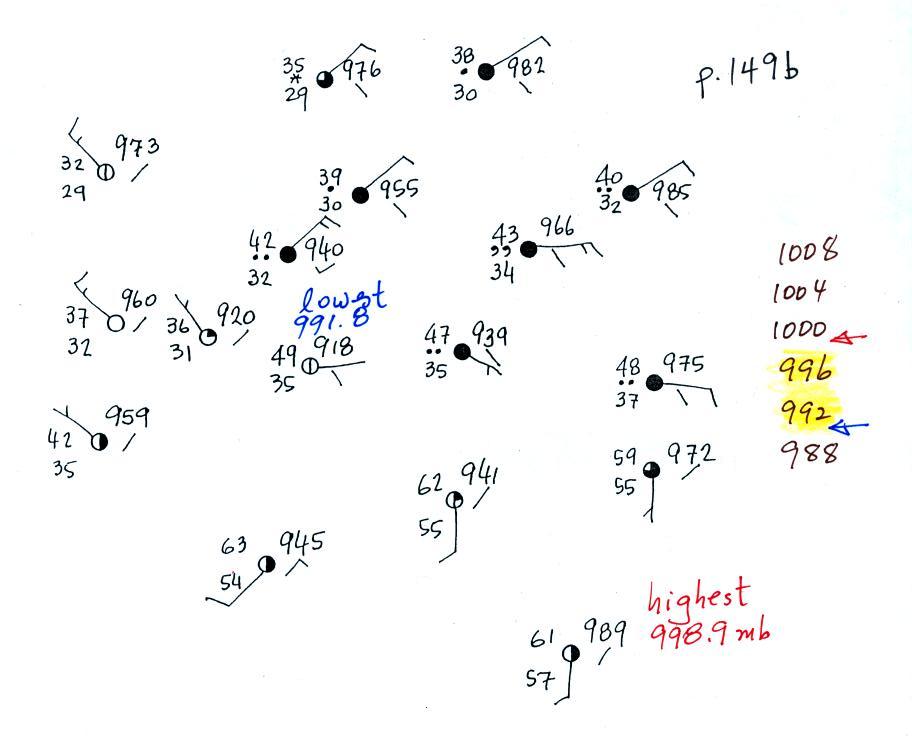

We've located located the highest and

lowest pressure values on the map. Then we choose

allowed isobar values that fall between these limits.

In this case we'll need to draw 992 mb and 996 mb isobars.

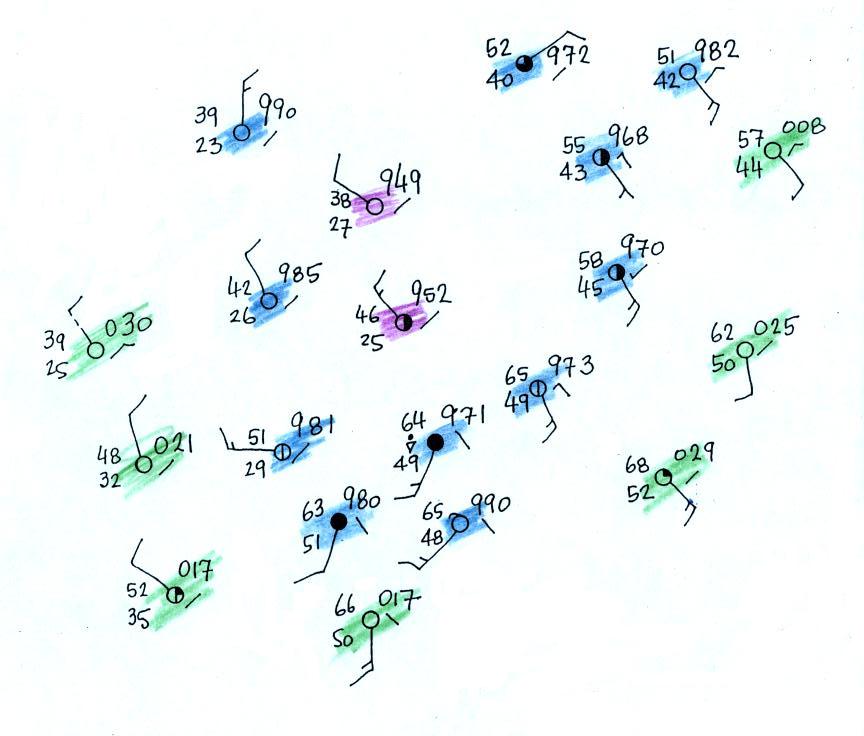

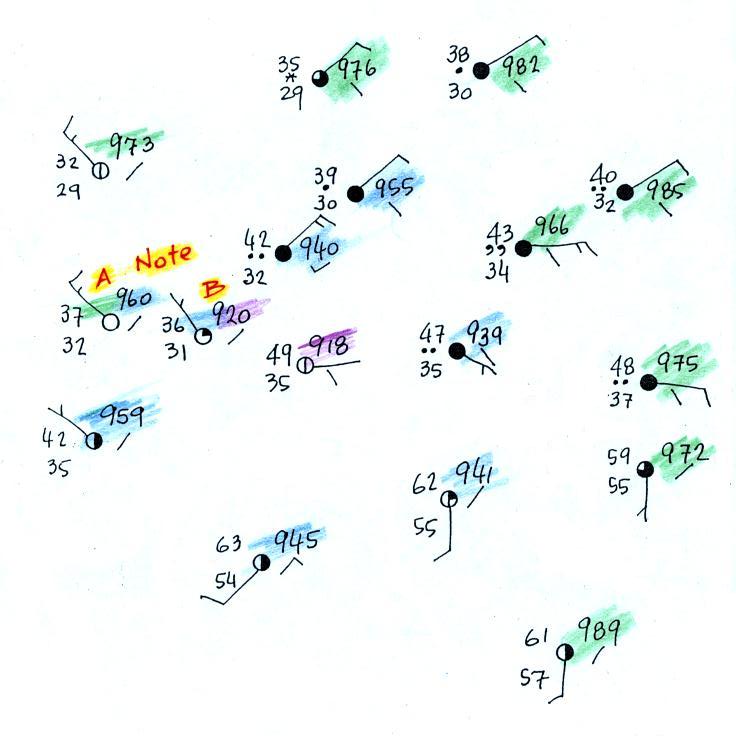

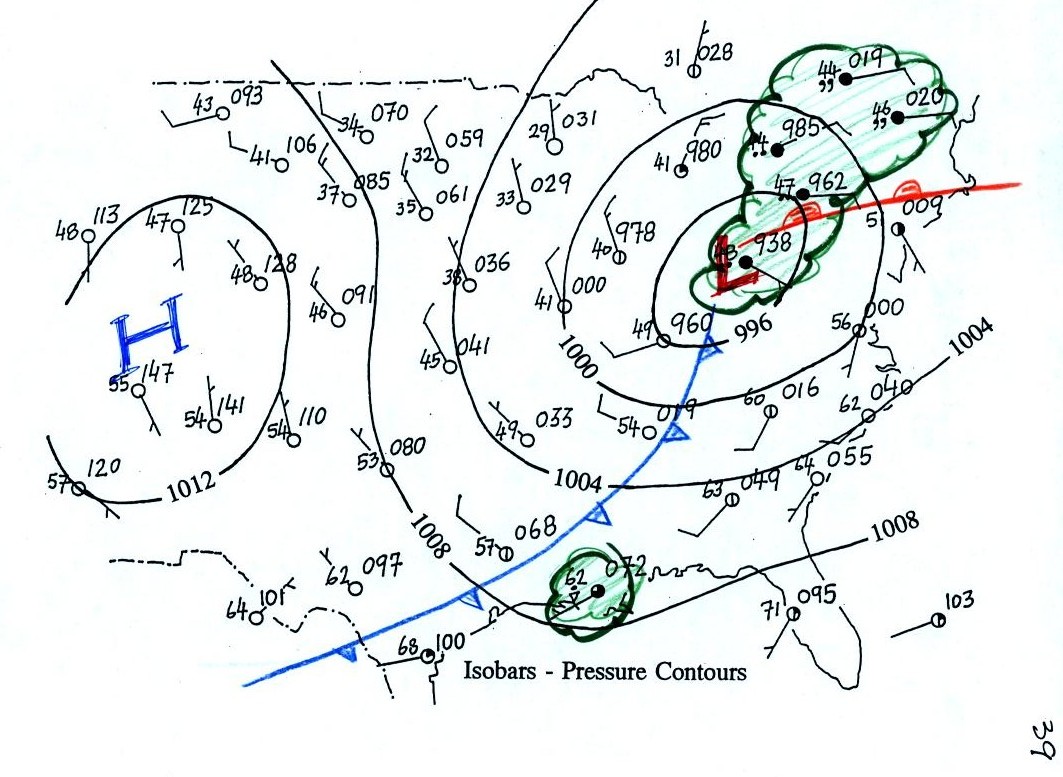

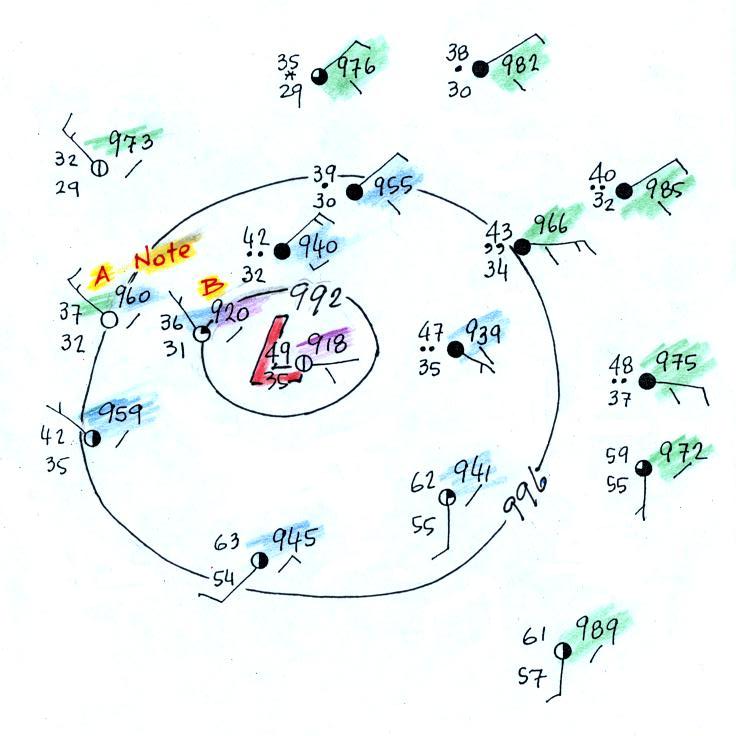

Here's the map with color coded pressures.

Pressures less than 992 mb are purple,

pressures between 992 and 996 mb are blue, and pressures greater

than 996 mb are green.

Note that station B has a pressure of exactly 992.0 mb, the

992 mb isobar will go through that station. The 996 mb

isobar will go through station A because it has a pressure

of exactly 996.0 mb.

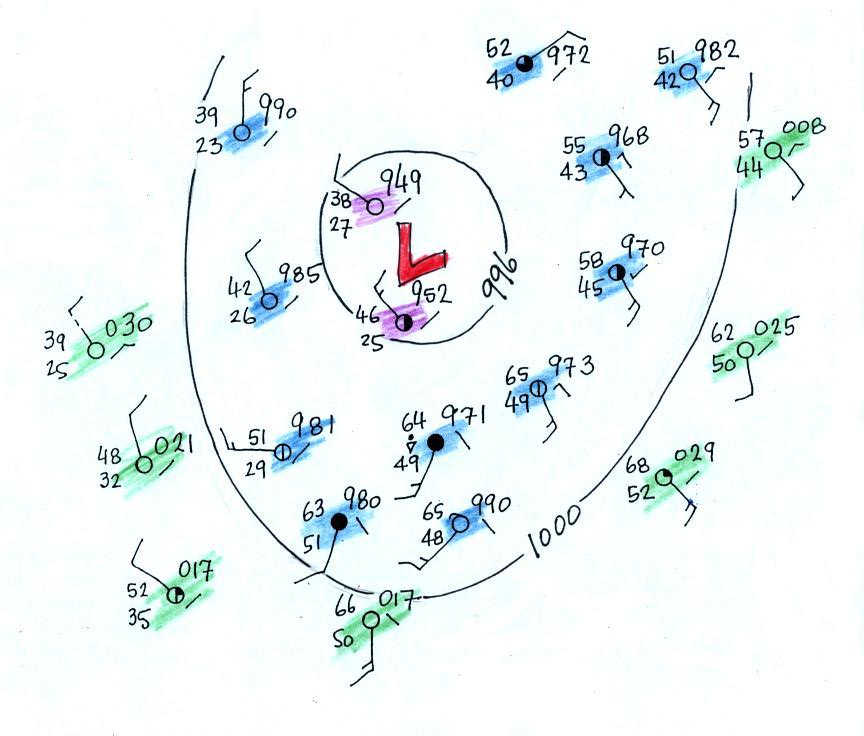

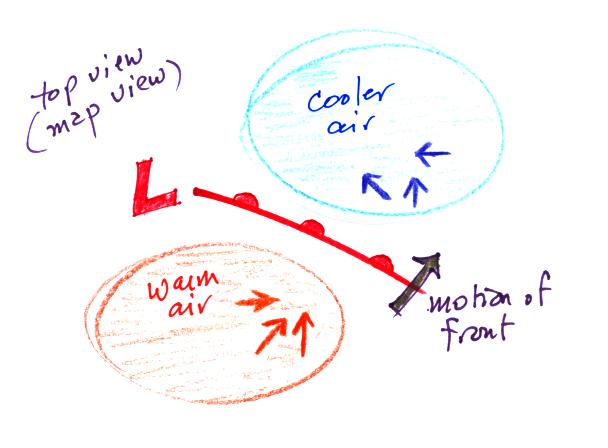

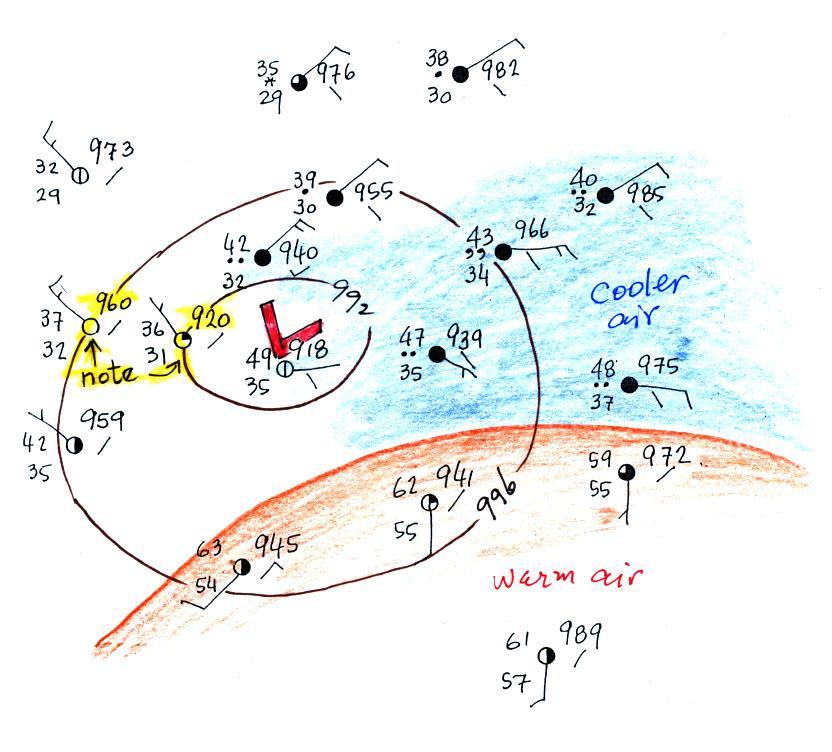

Here's the map with the isobars drawn

in. On the map below we use colors to locate the warm

and cooler air masses.

Step #2

The warm air mass has been colored in orange.

Cooler air east of the low pressure center is blue.

Can you see where the warm front should go?

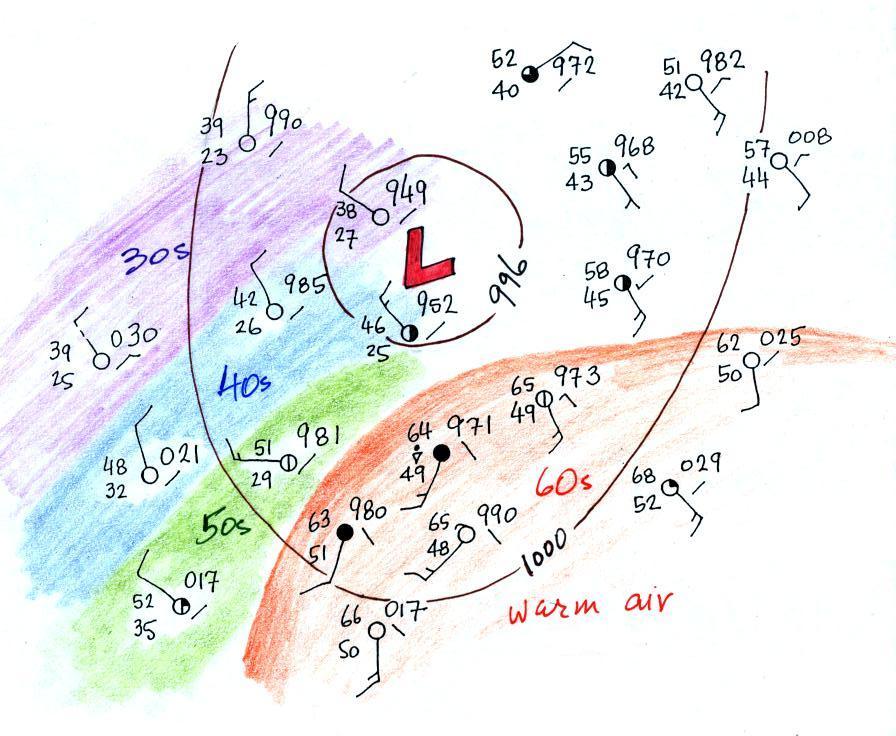

Step #3

Here's the map with a warm front drawn in

(the map was redrawn so that the edge of the warm

(orange) air mass would coincide with the warm

front).

The change in wind directions was probably

more pronounced than the temperature change. Most of the

clouds outlined in green are probably being produced by the

warm front. You can see how more extensive cloud

coverage is with a warm front.

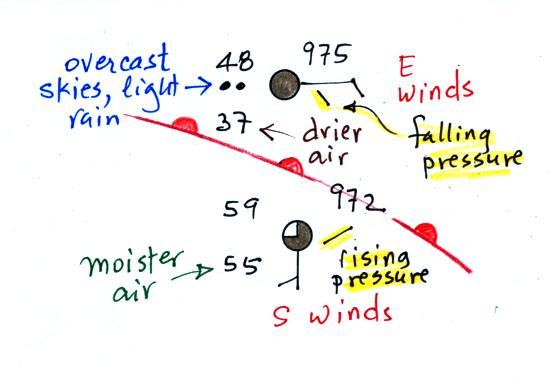

Step #4

Two of the stations near the right edge of the

picture and on opposite sides of the front are redrawn below.

The station north of the front has cooler and drier air,

winds are from the east, skies are overcast and light rain is

falling. The pressure is falling as the warm front

approaches. These are all things you'd expect to find

ahead of a warm front. Behind the front at the southern

station pressure is rising, the air is warmer and moister,

winds have shifted to the south and the skies are starting to

clear.

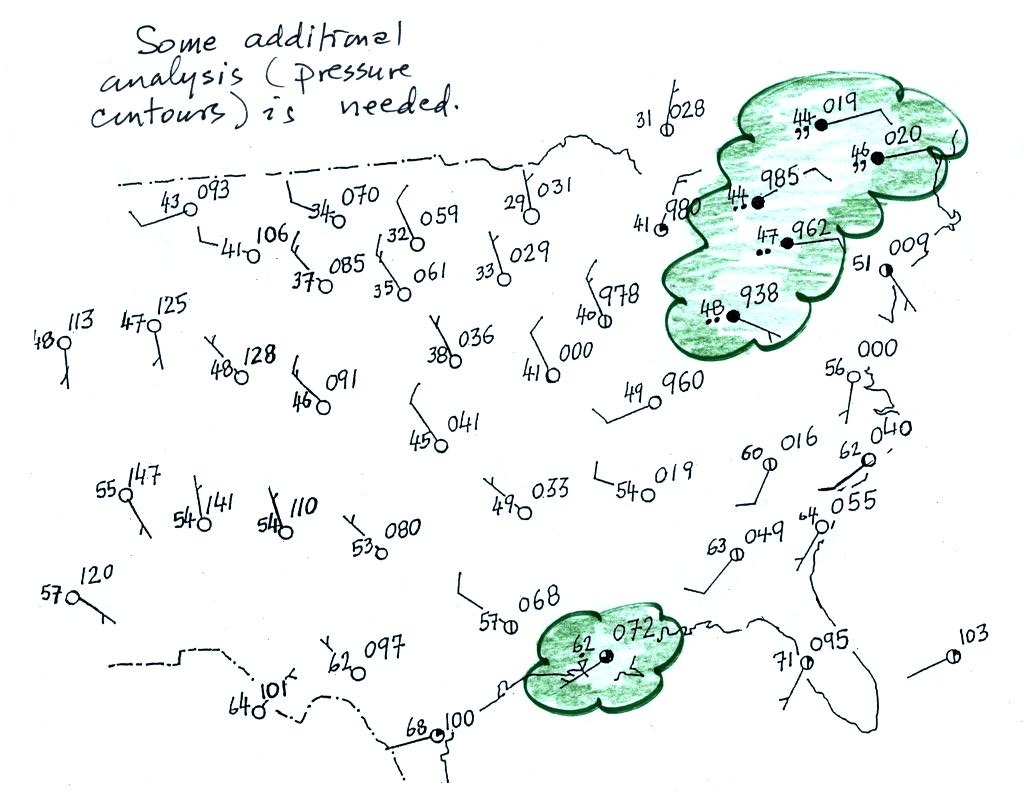

In this case there is a Step #5

Have a look at the left, western, side of the

map. There's pretty good evidence of a cold front.

There's a big temperature change (low 60s

to low 40s and 30s) and a very noticeable wind shift (SW ahead

of the cold front and NW behind).

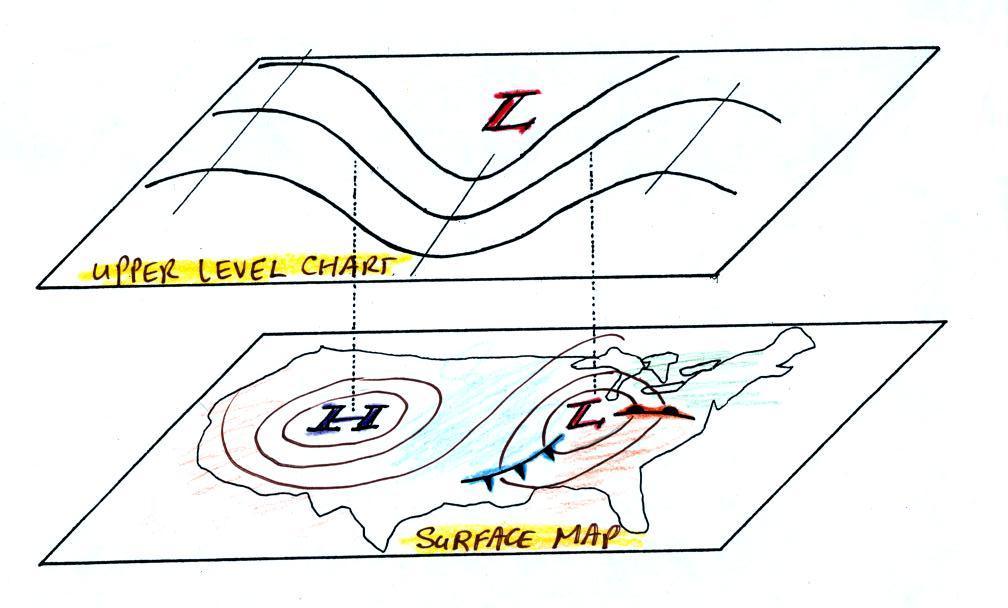

We need to go back to the figure where this

section on surface weather maps all began.

After learning how weather data are plotted

on a map using the station model notation we found that the

data, by themselves, were not enough to really be able to say

what was causing the cloudy, rainy weather in the NE and along

the Gulf Coast.

We added some isobars to reveal the pressure pattern and to

locate large centers of high and low pressure. Winds

converging into the center of low pressure cause air to rise

and might be part of the explanation for the unsettled weather

in the NE. That would explain the rain shower along the

Gulf Coast however.