Wednesday, Jan. 23, 2019

Sia: "California

Dreamin' " (3:37), "Chandelier"

(4:14), "Chandelier"

(4:05), "Midnight

Decisions" (3:44), "Breathe

Me" (4:55), "The

Girl You Lost to Cocaine" (3:58)

We'll be using page 23a,

page 23b, page 23c, page 23d, page 24a, and perhaps page 29 today from the

ClassNotes.

An Optional

(Extra Credit) Assignment was handed out in class today and

collected at the end of class. If you weren't in class, you

can download the assignment and turn it in at the beginning of

class on Friday.

Mass,

weight, density, and pressure.

Pressure

is a pretty important concept, that's what

we'll be working on today. Differences

in atmospheric pressure create winds which can

then cause storms. To better understand

pressure we need to first review mass and

weight.

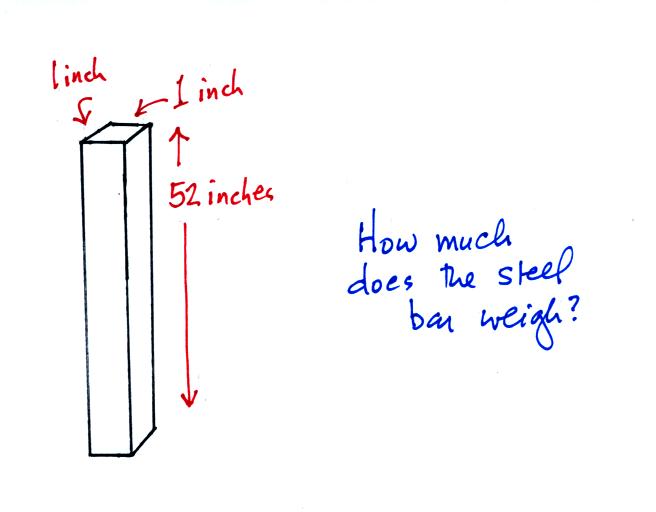

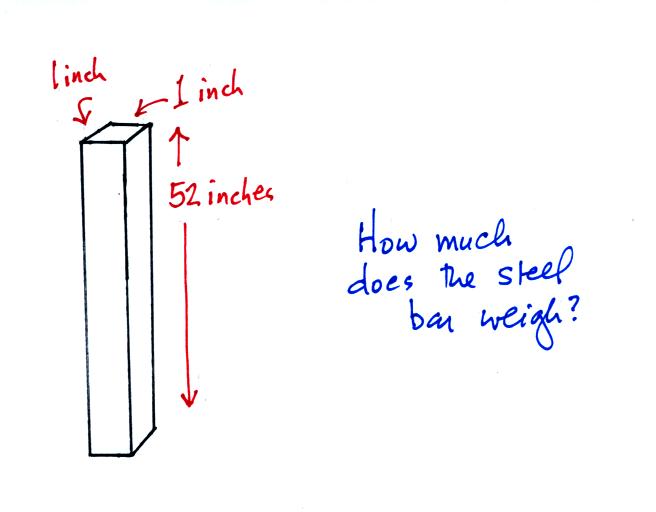

Weight is something you can feel. I'll

pass an iron bar around in class (it's

sketched below) - lift it and try to guess

it's weight. The fact that it is a 1" by

1" is significant. More about the bar

later in today's notes.

I used to

pass around a couple of small plastic bottles (see

below). One contained some water, the other an equal

volume of mercury (here's the source

of the nice photo of liquid mercury below at

right). I wanted you to appreciate how much

heavier and denser mercury is compared to

water.

But the plastic bottles have a way of getting brittle with

time and if the mercury were to spill in the classroom the

hazardous material people would need to come in and clean it

up. That would probably take a few days, would be very

expensive, and I would get into a lot of trouble. So

this semester I'll pass around a smaller, much safer, sample

of mercury so that you can at least see what mercury it looks

like (it's a recent purchase from a company in London).

I'll keep the plastic bottles of mercury up at the front of

the room just in case you want to see how heavy the stuff is.

It

isn't so much the liquid mercury that is a hazard, but

rather the mercury vapor. Mercury vapor is used in

fluorescent bulbs (including the new energy efficient CFL

bulbs) which is why they need to be disposed of properly

(you shouldn't just throw them in the dumpster).

That is a topic that will come up again later in the

class. Mercury

and bromine are the only two elements that are found

naturally in liquid form. All the other elements are

either gases or solids.

I am hoping that you will remember and understand the

following statement

atmospheric

pressure at any level in the atmosphere

depends on (is determined by)

the weight

of the air overhead

We'll

first review the concepts of mass, weight, and density

but understanding pressure is our main goal.

I've numbered the various sections to help with

organization. There's a summary at the end of

today's notes.

1.

weight

This is a good place to start because this is

something we are pretty familiar with. We

can feel weight and we routinely measure weight.

A person's weight also depends

on something else.

In outer space away from

the pull of the earth's gravity people are weightless.

Weight depends on the person and on the pull of gravity.

We

measure weight all the

time. What units

do we use?

Usually pounds, but

sometimes ounces or

maybe tons.

Students sometimes

mention Newtons, those

are metric units of

weight (force).

2. mass

Rather than just saying the

amount of something it is probably better to use the

word mass

It would be possible to have equal volumes of

different materials or the same total number of atoms or

molecules of two different materials, and still have different

masses.

Grams (g) and kilograms (kg) are commonly used units of

mass (1 kg is 1000 g). They're metric units (slugs are

the units of mass in the English (American) system of units).

3. gravitational

acceleration

On the surface of the earth, weight is

mass times a constant, g, known as the

gravitational acceleration. The value of g

is what tells us about the strength of gravity on the earth;

it is determined by the size and mass of the earth. On

another planet the value of g would be

different. If you click here

you'll find a little (actually a lot) more information about

Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation. You'll see how

the value of g is determined and why it is called

the gravitational acceleration. These aren't details

you need to worry about but they're there just in case

you're curious.

Here's a question to test your understanding.

The masses are all the same. On the earth's surface the

masses would all be multiplied by the same value of g.

The weights would all be equal. If

all 3 objects had a mass of 1 kg, they'd all have a weight of 2.2

pounds. That's why we can use

kilograms and pounds interchangeably.

The following figure show a situation where two

objects with the same mass would have different weights.

On the earth a brick has a mass of about

2.3 kg and weighs 5 pounds. If you were to travel to the

moon the mass of the brick wouldn't change (it's the same

brick, the same amount of stuff). Gravity on the moon is

weaker (about 6 times weaker) than on the earth because the

moon is smaller and it has less mass, the value of g

on the moon is different than on the earth. The brick

would only weigh 0.8 pounds on the moon.

The brick would weigh almost 12 pounds on the surface on

Jupiter where gravity is stronger than on the earth.

On the moon, a brick would have the same mass, the same

volume, the same density, but a different weight as(than)

it would on the earth.

The three objects below

were not passed around class (one of them is pretty

heavy). The three objects all have about

the same volumes. One is a piece of wood,

another a brick, and the third is something

else.

The

easiest way to determine which is which is to lift each

one. One of them weighed about 1 pound (wood), the 2nd

about 5 pounds (a brick) and the last one was 15 pounds (a

block of lead).

The point of all this was to get you thinking about

density. Here we had three objects of about

the same size with very different weights. Different

weights means the objects have different masses (since weight

depends on mass). The three different masses, were

squeezed into roughly the same volume producing objects of

very different densities.

4. density

The brick is in the back, the lead

on the left, and the piece of wood (redwood) on the right.

The wood is less dense than water (see the table below) and

will float when thrown in water. The brick and the lead

are denser than water and would sink in water.

We'll be more concerned with air in this

class than wood, brick, or lead.

In the first example

below we have two equal volumes of air but the amount

(mass) of air squeezed into each volume is different (the

dots represent air molecules).

The amounts of air (the masses) in the second example are the

same but the volumes are different. The left example

with air squeezed into a smaller volume has the higher

density.

material

|

density g/cc

|

air

|

0.001

|

redwood

|

0.45

|

water

|

1.0

|

iron

|

7.9

|

lead

|

11.3

|

mercury

|

13.6

|

gold

|

19.3

|

platinum

|

21.4

|

iridium

|

22.4

|

osmium

|

22.6

|

g/cc = grams per cubic centimeter

cubic centimeters are units of volume - one cubic

centimeter is about the size of a sugar cube

1 cubic centimeter is also 1 milliliter (mL)

I would sure like to get my hands on a brick-size

piece of iridium or osmium just to be able to feel how

heavy it would be - it's about 2 times denser than

lead.

Here's a more subtle concept. What if you were in outer

space with the three wrapped blocks of lead, wood, and

brick? They'd be weightless.

Could you tell them apart then? They would still have very

different densities and masses but we wouldn't be able to feel how

heavy they were.

5.

inertia

I think the following illustration will

help you to understand inertia.

Two stopped cars. They are the same size except

one is made of wood and the other of lead. Which

would be hardest to get moving (a stopped car resists

being put into motion). It would take considerable

force to get the lead car going. Once the cars are

moving they resist a change in that motion. The

lead car would be much harder to slow down and stop.

This is the way you could try to distinguish

between blocks of lead, wood, and brick in outer space.

Give them each a push. The wood would begin moving more

rapidly than the block of lead even if both are given

the same strength push.

I usually

don't mention in class that this concept of

inertia comes from Newton's 2nd law of motion

F = m a

force = mass x acceleration

We can rewrite the equation

a = F/m

This shows cause and effect more clearly. If you exert a

force (cause) on an object it will accelerate (effect).

Acceleration can be a change in speed or a change in direction (or

both). Because the mass is in the denominator, the

acceleration will be less when mass (inertia) is large.

Here's where we're at

From left to right the brick, the iron bar, the piece

of wood, and the lead block. They're all standing on end.

The weight of the iron bar is still unknown.

Now

we're close to

being ready to

define (and

hopefully

understand)

pressure.

It's a pretty

important

concept.

A lot of what

happens in the

atmosphere is

caused by

pressure

differences.

Pressure

differences

cause

wind.

Large pressure

differences

(such as you

might find in

a tornado or a

hurricane) can

create strong

and

destructive

storms.

The air that surrounds the earth has mass. Gravity pulls

downward on the atmosphere giving it weight. Galileo

conducted a

simple experiment to prove that air has weight (in the

1600s).

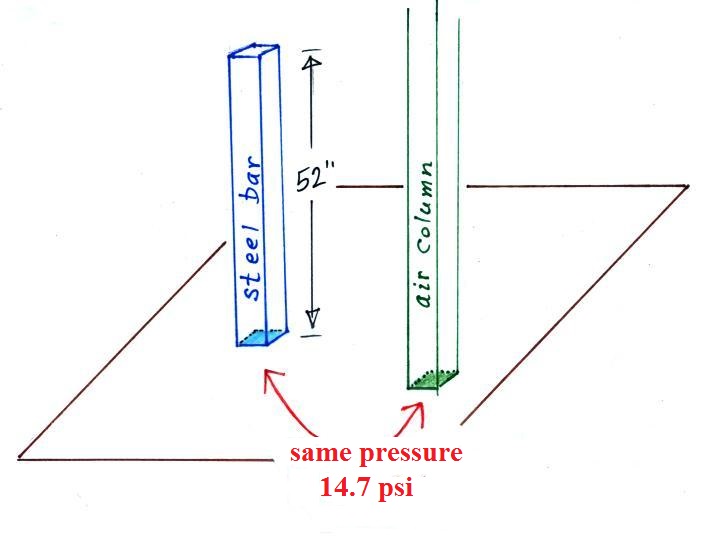

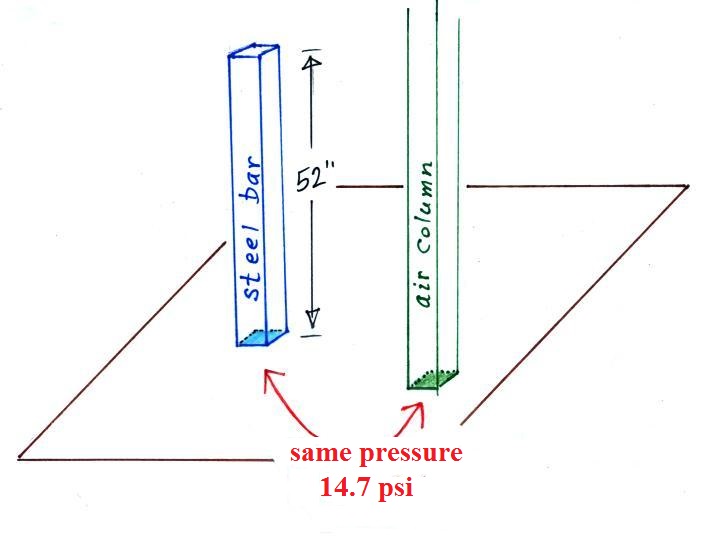

We

could add a very

tall 1 inch x 1

inch column of air

to the

picture.

Other than being a

gas, being

invisible, and

having much lower

density, it's

really no

different from the

other objects.

6. pressure

Atmospheric pressure at

any level in the atmosphere

depends on (is determined

by)

the weight of the air

overhead

This

is one way, a sort of large scale, atmosphere size

scale, way of understanding air pressure.

Pressure depends on, is determined by, the weight of the

air overhead. To determine the pressure you need to

divide by the area the weight is resting on.

and here we'll apply the

definition to a column of air stretching from sea

level to the top of the atmosphere (the figure below

is on page 23d

in the ClassNotes)

Pressure is defined as force divided by area. Atmospheric

pressure is the weight of the air column divided by the area at

the bottom of the column (as illustrated above).

Under normal conditions a 1 inch by 1 inch column of air

stretching from sea level to the top of the atmosphere will weigh

14.7 pounds.

Normal atmospheric pressure at sea level is 14.7 pounds per square

inch (psi, the units you use when you fill up your car

or bike tires with air).

Now back to the iron bar. The bar actually weighs

14.7 pounds (many people I suspect think it's heavier than

that). When you stand the bar on end, the pressure at

the bottom would be 14.7 psi.

The weight of the 52 inch

long 1" x 1" steel bar is the same as a 1" x 1" column

of air that extends from sea level to the top of the

atmosphere 100 or 200 miles (or more) high. The

pressure at the bottom of both would be 14.7 psi.

7. pressure units

Pounds per square inch, psi, are

perfectly good pressure units, but they aren't the ones

that meteorologists use most of the time.

Typical sea

level pressure is 14.7 psi or about 1000 millibars

(the units used by meteorologists and the units that we will

probably mostly use in this class) or about 30 inches of

mercury (refers to the reading on a mercury

barometer). Milli means 1/1000 th. So

1000 millibars is the same as 1 bar. You sometimes see

typical sea level pressure written as 1 atmosphere.

Summary

Average and record

setting sea level pressure values

Sea level pressure averages about 1000 mb but it changes

and can be higher or lower than that.

The simple figure above at left contains

just the essential information. Focus on and try to

remember that. A lot more information and details have

been added to the figure at right.

Sea level pressure values usually fall between 950 mb and

1050 mb.

Record HIGH level sea pressure values occur during cold

winter weather. The TV weather forecast

will often associate hot weather with high pressure.

This might seem contradictory but they are generally

referring to upper level high pressure (high pressure at

some level above the ground) rather than surface pressure.

You'll sometimes hear this upper level high pressure

referred to as a ridge, we'll learn more about this later in

the semester.

Record setting LOW sea level pressure values are found in

the centers of strong hurricanes.

Hurricane Wilma in 2005 set a new record low sea level

pressure reading for the Atlantic, 882 mb. Hurricane

Katrina earlier in the same year had a pressure of 902

mb. The table below lists some information on intense

hurricanes. 2005 was a very unusual year, 3 of the 10

strongest N. Atlantic hurricanes ever occurred in

2005. There were also a record number of Atlantic

hurricanes in 2005. The strongest Atlantic

hurricanes from 2017 have been added. 2017 was the

costliest hurricane season on record in the United States

and the deadliest since 2005.

Hurricane Patricia off the west coast of Mexico in fall

2015 set a new surface low pressure record for the Western

Hemisphere - 872 mb and very close to the world

record. Sustained winds of 200 MPH were observed in

that storm.

Most

Intense North Atlantic Hurricanes

|

Most

Intense Hurricanes

to hit the US Mainland

|

Wilma

(2005) 882 mb

Gilbert (1988) 888 mb

1935 Labor Day 892 mb

Rita (2005) 895 mb

Allen (1980) 899

Katrina (2005) 902

|

1935

Labor Day 892 mb

Camille (1969) 909 mb

Katrina (2005) 920 mb

Andrew (1992) 922 mb

1886 Indianola (Tx) 925 mb |

strong 2017 hurricanes

|

Harvey 937 mb

Irma 914 mb

Jose 938 mb

Maria 908 mb

|

What makes hurricane winds so strong is the pressure gradient,

i.e. how quickly pressure changes with distance (horizontal

distance). Pressure can drop from near average values

(1000 mb) at the edges of the storm to the low values shown

above at the center of the storm.

Low pressure is also found in the centers of

tornadoes. A surface pressure value of 850 mb was

measured in 2003 inside a strong tornado in Manchester, South

Dakota (https://www.weather.gov/fsd/20030624-tornadosamaras).

This is a very difficult (and very dangerous) thing to try to

do. Not only must the instruments be built to survive a

tornado but they must also be placed on the ground ahead of an

approaching tornado and the tornado must then pass over the

instruments (also the person placing the instrument needs to

get out of the way of the approaching tornado).

You can experience pressure values much lower than that

(roughly 700 mb) by simply driving up to Mt. Lemmon.

Pressure changes much more quickly if you move vertically in

the atmosphere than if you move sideways. Very strong

vertical changes in pressure are usually almost balanced

exactly by gravity.