Mon., May 1, 2006

Grade summaries will be held hostage until someone volunteers to

conduct the course evaluation.

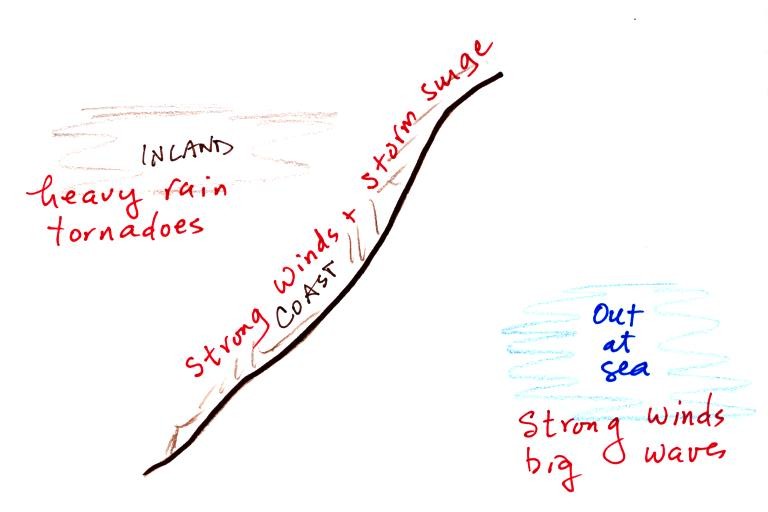

Hurricanes are now alternately given male and female names.

The

names start with A (a male name one year, a female name starting with A

the next year) at the start of

every new storm season. Five letters (Q, U, X, Y, and Z) are not

included in the list. In 2005 in the N. Atlantic they ran out of

letters of the alphabet and 6 Greek characters had to be used (Alpha,

Beta, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, and Zeta). The last storm of 2005

actually remained active into Jan. 2006.

The list of names repeats every 6 years, though the names of unusually

strong or destructive hurricanes may be retired. There were 5

names retired following the 2005 N. Atlantic hurricane season (Dennis,

Katrina, Rita, Stan, & Wilma).

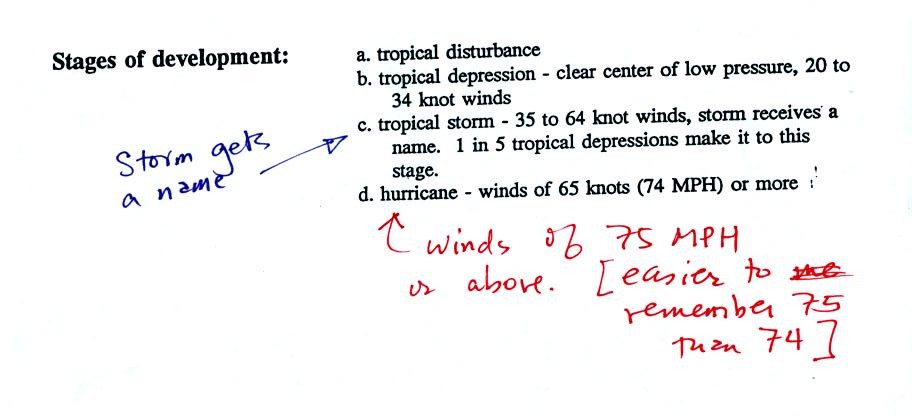

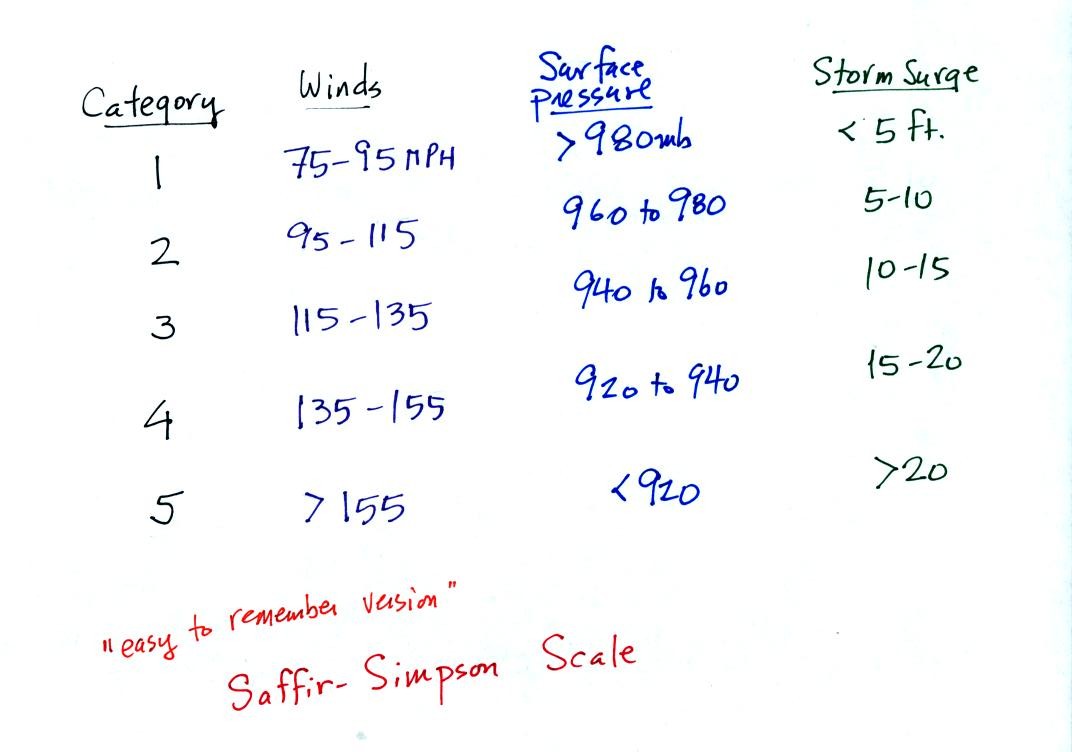

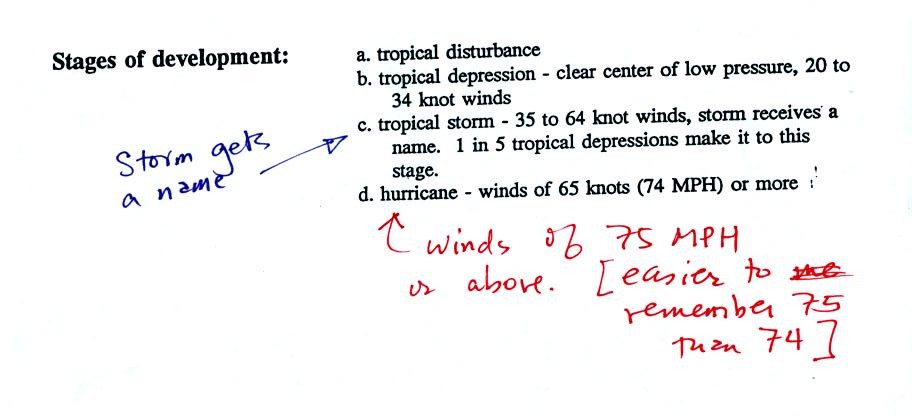

Here is an easy to remember version of the Saffir Simpson

scale used to

classify hurricane strength and damage potential.

If you remember that winds must be 75 MPH or higher in order for a

tropical cyclone to be a hurricane. In this easy to remember

scale the winds increase by 20 MPH as you move up the scale.

Pressures decrease in 20 mb increments (start at 1000 mb and go down

from there) and the height of the storm

surge increases by 5 feet. It is thought that parts of the

Louisianna and Mississippi coasts were hit with a 30 ft. storm surge as

Hurricane Katrina moved onshore last year.

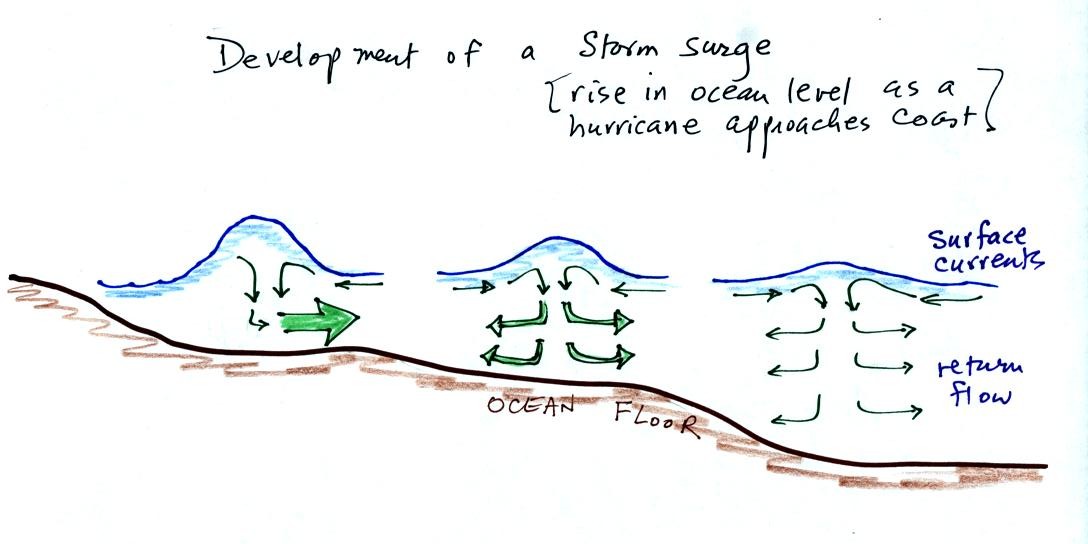

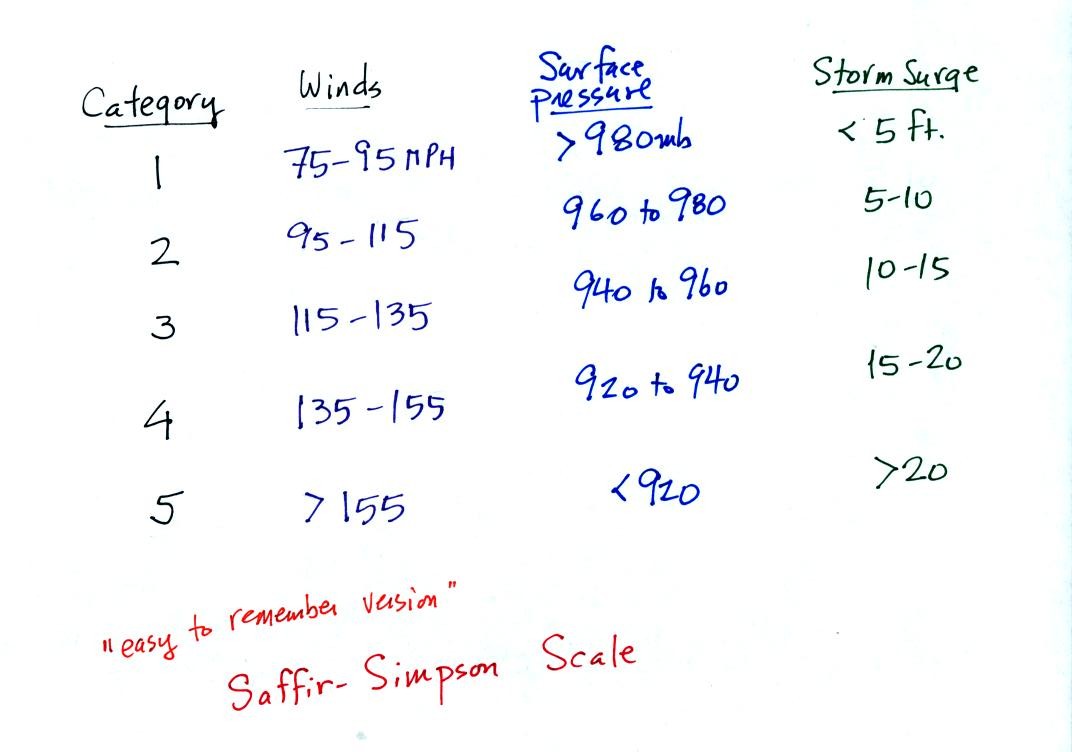

Out at sea, the converging surface winds create surface currents

in the

ocean that transport water toward the center of the hurricane.

The rise in ocean level is probably only a few feet, though the waves

are much larger. A return flow develops underwater that carries

the water back to where it came from.

As the hurricane approaches shore, the ocean becomes shallower.

The return flow must pass through a more restricted space. A rise

in ocean level will increase the underwater pressure and the return

flow will speed up. More pressure and an even faster return flow

is needed as the hurricane gets near the coast.

Here is a link to the storm surge website

(from the Hurricane Research Division of the Atlantic Oceanographic and

Meteorological Labororatory). It has an interesting animation

showing output from the SLOSH model used to predict hurricane storm

surges.

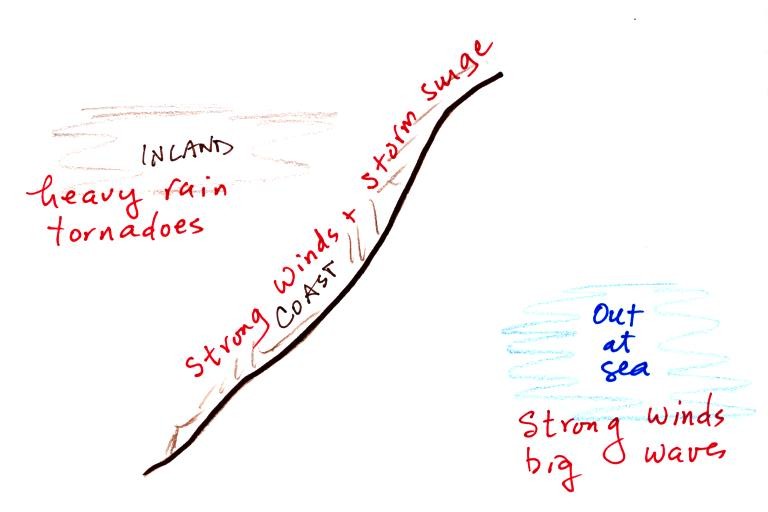

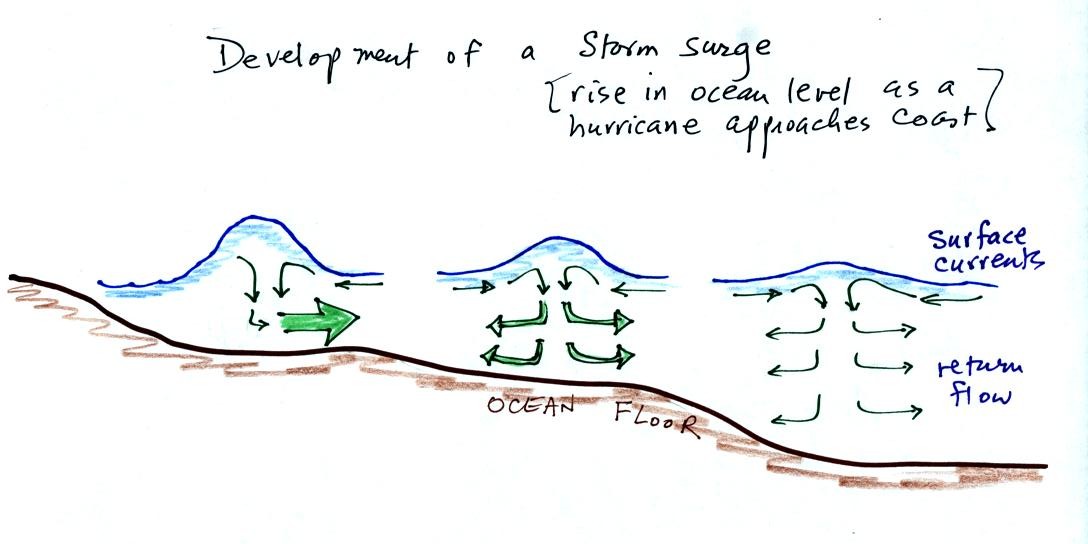

Hurricanes can, of course, be very destructive. Out at

sea the

main hazards are the strong winds and the large waves. The

Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger describes the sinking of the Andrea

Gail in a strong hurricane like storm in October 1991. The exact

fate of the fishing ship is not known but it may have been turned end

over end by a large wave (pitch poled). Large waves can also

flood a ship and begin to fill it with water.

Along a coast the greatest threat is from the hurricane winds and the

storm surge. Large waves are superimposed on the storm surge.

The hurricanes winds slow quickly as it moves onshore, though

tornadoes may form. The biggest threat is from flooding.

Hurricanes can easily drop a foot or more of rain on an area as they

pass through.

Some of

the record setting values listed on p. 145 in the photocopied

notes are now going to have to be changed. Hurricane GILBERT

(1988) no longer holds the record for the lowest sea level surface

pressure reading in the Atlantic. That record now belongs to

Hurricane WILMA (882 mb). Peak winds in Hurricane Wilma reached

185 MPH.

Hurricane ANDREW (1992) is no longer the most expensive natural

disaster in US history. That record now belongs to Hurricane

KATRINA and is up to about $75B over three times that of Andrew.

The 1900 Galveston hurricane still remains the deadliest natural

disaster in US history. Hurricane MITCH remains the deadliest

hurricane in the N. Atlantic in over 200 years. More than 20,000

people are now thought to have been killed in Central America during

Hurricane MITCH.