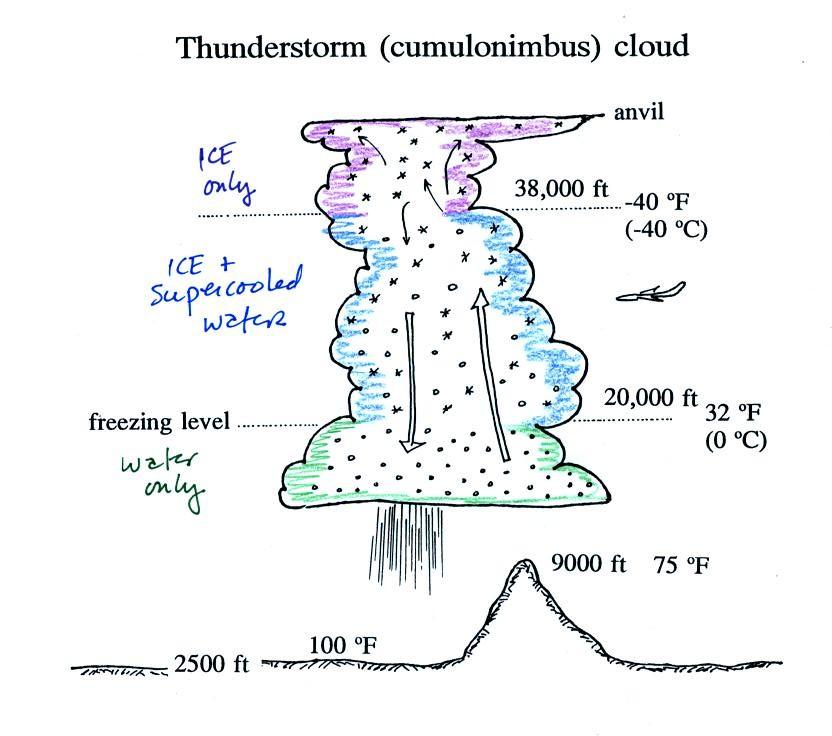

A typical summer

thunderstorm in Tucson is shown in the figure

above (p. 165 in the photocopied ClassNotes). Even

on the hottest day in Tucson in the summer a large part of

the middle of the cloud is found at below freezing

temperatures and contains a mixture of super cooled water

droplets and ice crystals. This is where

precipitation forms and is also where electrical charge is

created. Doesn't it seem a little unusual that

electricity, static electricity, can be created in the wet

interior of a thunderstorm?

1. What produces the electrical charge needed for lightning?

2. Different types of lightning

1. What produces the electrical charge needed for lightning?

2. Different types of lightning

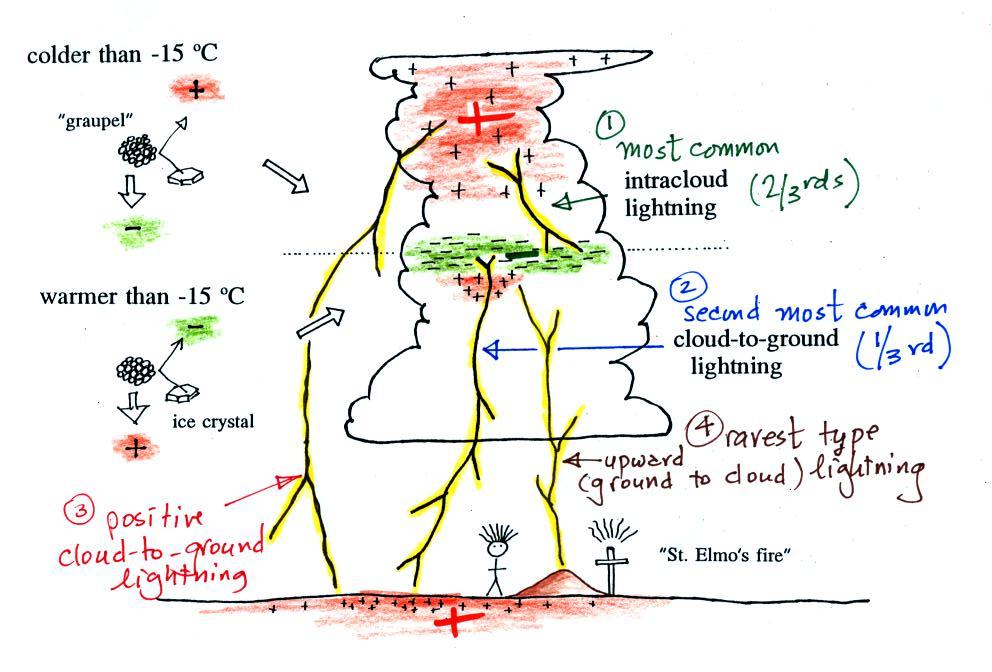

Collisions between precipitation

particles produce the electrical charge needed for

lightning. When temperatures are

colder than -15 C (above the dotted line in the figure

above), graupel becomes negatively charged after colliding

with a snow crystal. The snow crystal is positively

charged and, because it is smaller and lighter, is carried

up toward the top of the cloud by the updraft winds.

At temperature warmer than -15 (but still below freezing),

the polarities are reversed. A large volume of

positive charge builds up in the top of the

thunderstorm. A layer of negative charge accumulates

in the middle of the cloud. Some smaller volumes of

positive charge are found below the layer of negative

charge. Positive charge also builds up in the ground

under the thunderstorm (it is drawn there by the large

layer of negative charge in the cloud).

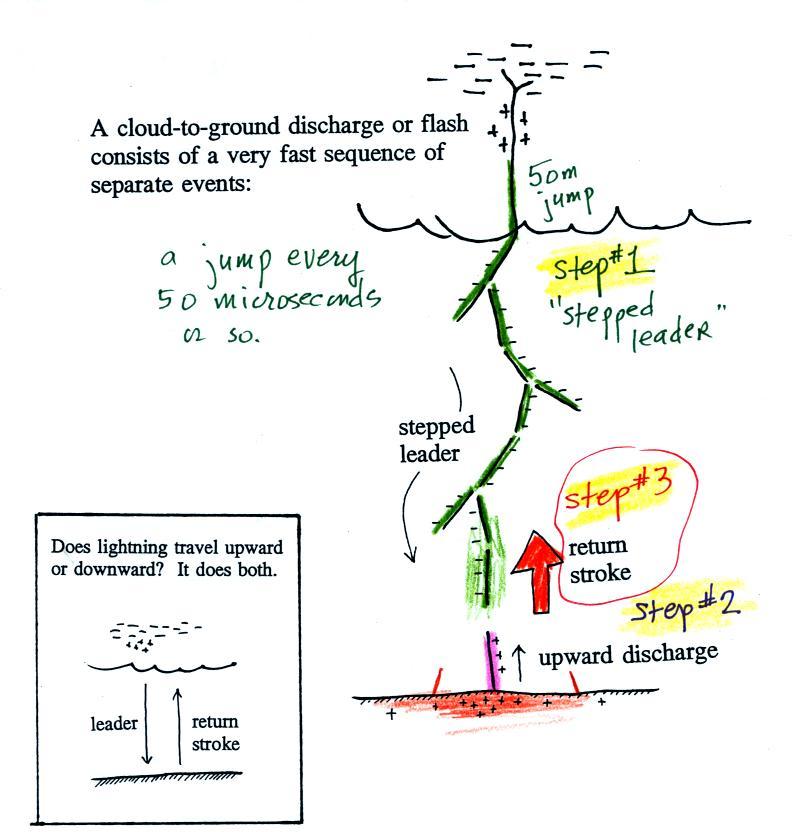

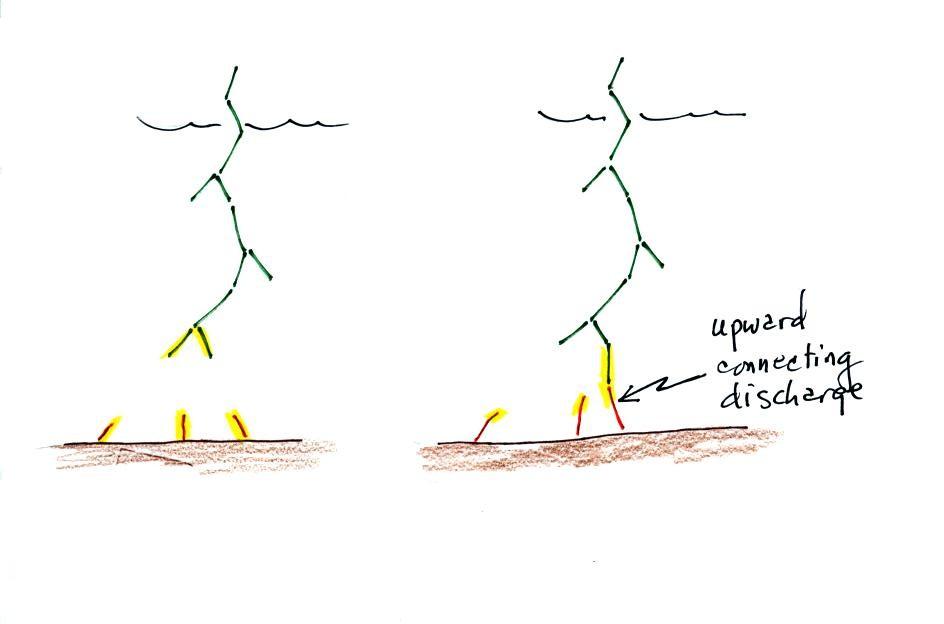

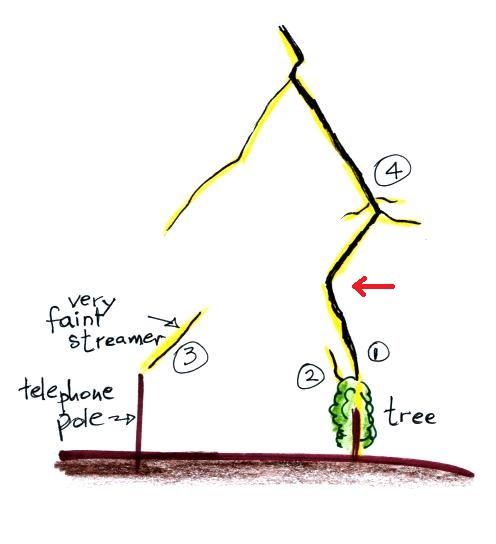

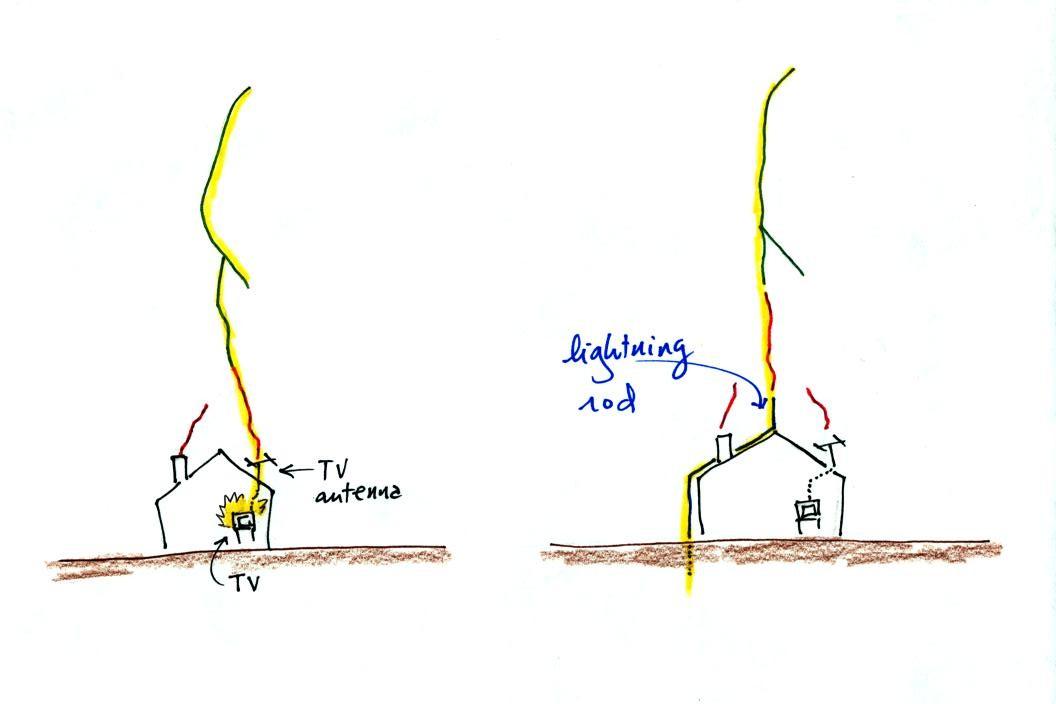

Air is normally an insulator, but when the electrical attractive forces between the volumes of charge in the cloud gets gets high enough lightning occurs. Most lightning (2/3 rds, maybe even 3/4) stays inside the cloud and travels between the main positive charge center near the top of the cloud and the layer of negative charge in the middle of the cloud; this is intracloud lightning (Pt. 1). About 1/3 rd of all lightning flashes strike the ground. These are called cloud-to-ground discharges (actually negative cloud-to-ground lightning). We'll spend most of the class learning about this particular type of lightning (Pt. 2). It's what kills people and starts forest fires. A photograph of a negative cloud to ground flash is shown below at left.

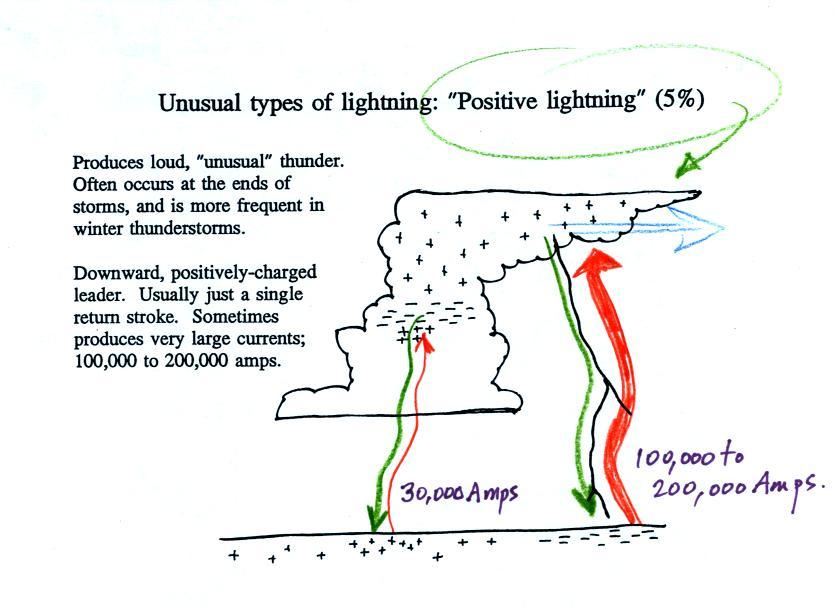

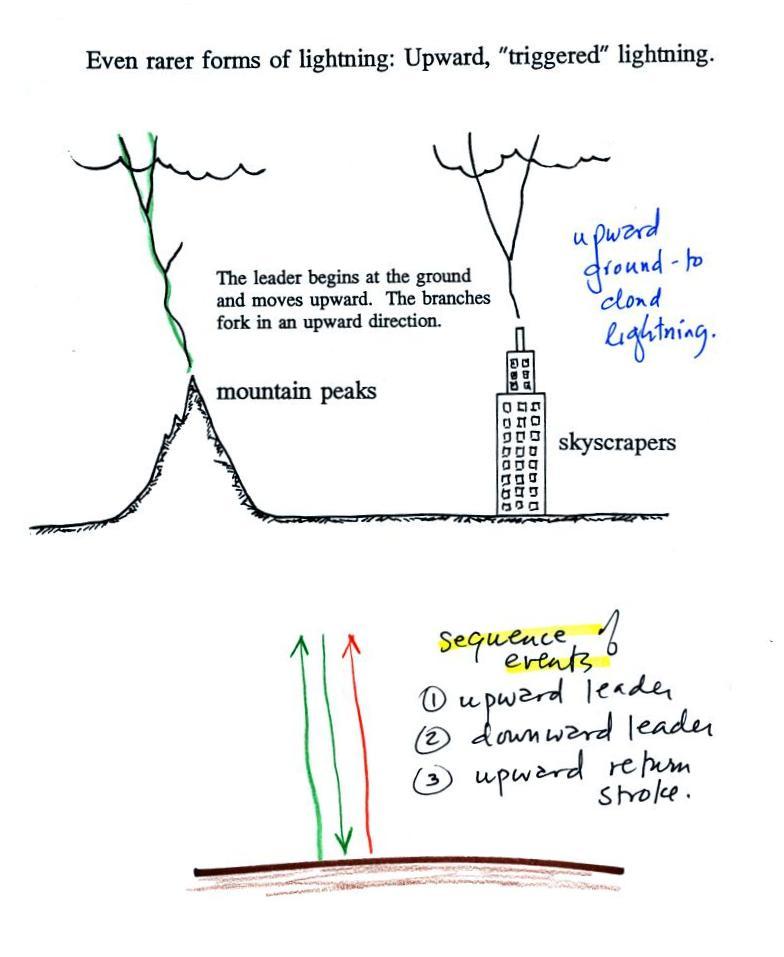

Positive polarity cloud to ground lightning (Pt. 3) accounts for a few percent of lightning discharges. Upward lightning is the rarest form of lightning (Pt. 4). The photo below at right shows an upward lightning discharge that was initiated by the Eiffel Tower in Paris. We'll look at both of these unusual types of lightning later in the class.

Air is normally an insulator, but when the electrical attractive forces between the volumes of charge in the cloud gets gets high enough lightning occurs. Most lightning (2/3 rds, maybe even 3/4) stays inside the cloud and travels between the main positive charge center near the top of the cloud and the layer of negative charge in the middle of the cloud; this is intracloud lightning (Pt. 1). About 1/3 rd of all lightning flashes strike the ground. These are called cloud-to-ground discharges (actually negative cloud-to-ground lightning). We'll spend most of the class learning about this particular type of lightning (Pt. 2). It's what kills people and starts forest fires. A photograph of a negative cloud to ground flash is shown below at left.

Positive polarity cloud to ground lightning (Pt. 3) accounts for a few percent of lightning discharges. Upward lightning is the rarest form of lightning (Pt. 4). The photo below at right shows an upward lightning discharge that was initiated by the Eiffel Tower in Paris. We'll look at both of these unusual types of lightning later in the class.

|

|

| Cloud to ground lightning with

downward branching (source

of this photo) |

An upward lightning discharge

initiated by the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

The branching, visible at the top of the

photograph, is upward. Photographed by Hakim

Atek, source

of this photo |

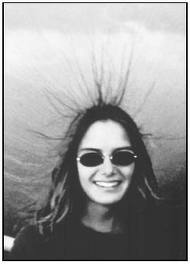

A couple of interesting things can happen at the ground under a thunderstorm. Attraction between positive charge in the ground and the layer of negative charge in the cloud can become strong enough that a person's hair will literally stand on end (see two photos below). This is incidentally a very dangerous situation to be in; I wouldn't wait around for my picture to be taken.

|

|

St. Elmo's Fire (corona discharge) is a faint electrical discharge that sometimes develops at the tops of elevated objects during thunderstorms. The link will take you to a site that shows corona discharge. Have a look at the first 3 pictures, they probably resemble St. Elmo's fire. The remaining pictures are probably different phenomena. St. Elmo's fire was first observed coming from the tall masts of sailing ships at sea (St. Elmo is the patron saint of sailors). Sailors in those days were often very superstitious and I suspect they found St. Elmo's fire pretty terrifying.