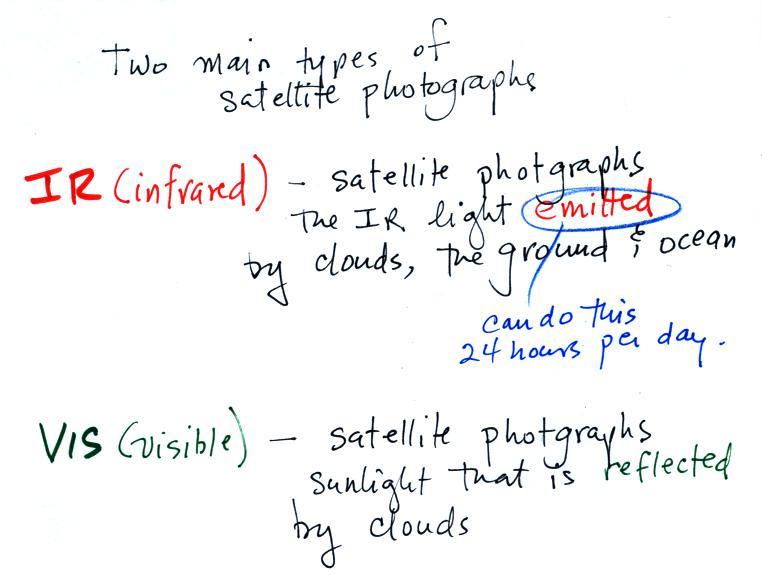

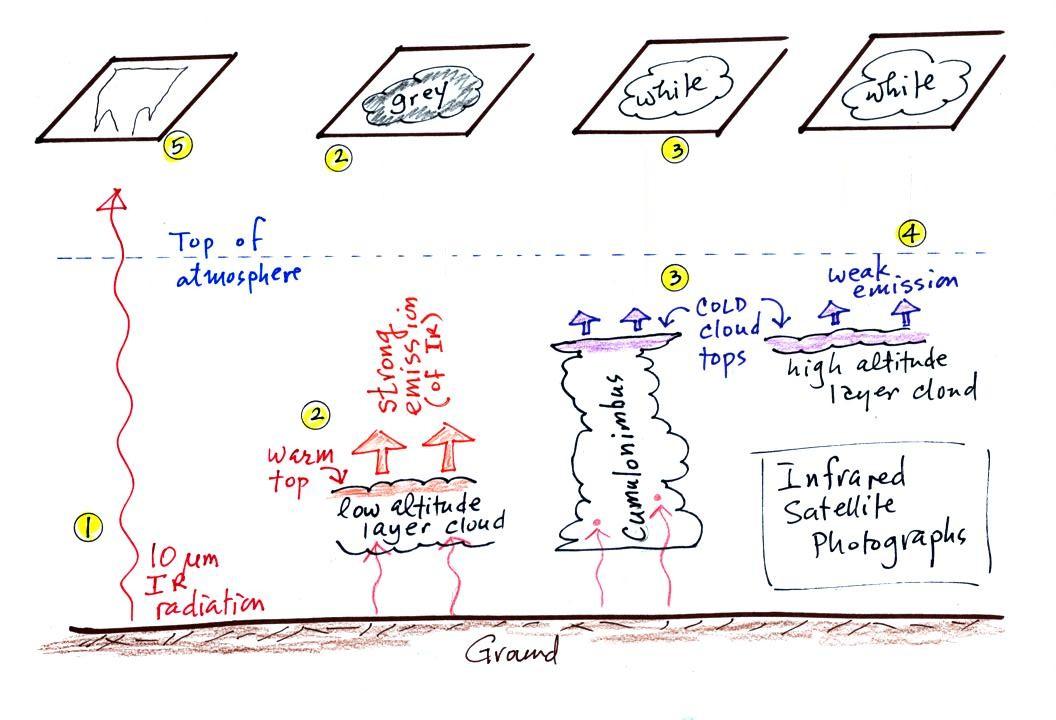

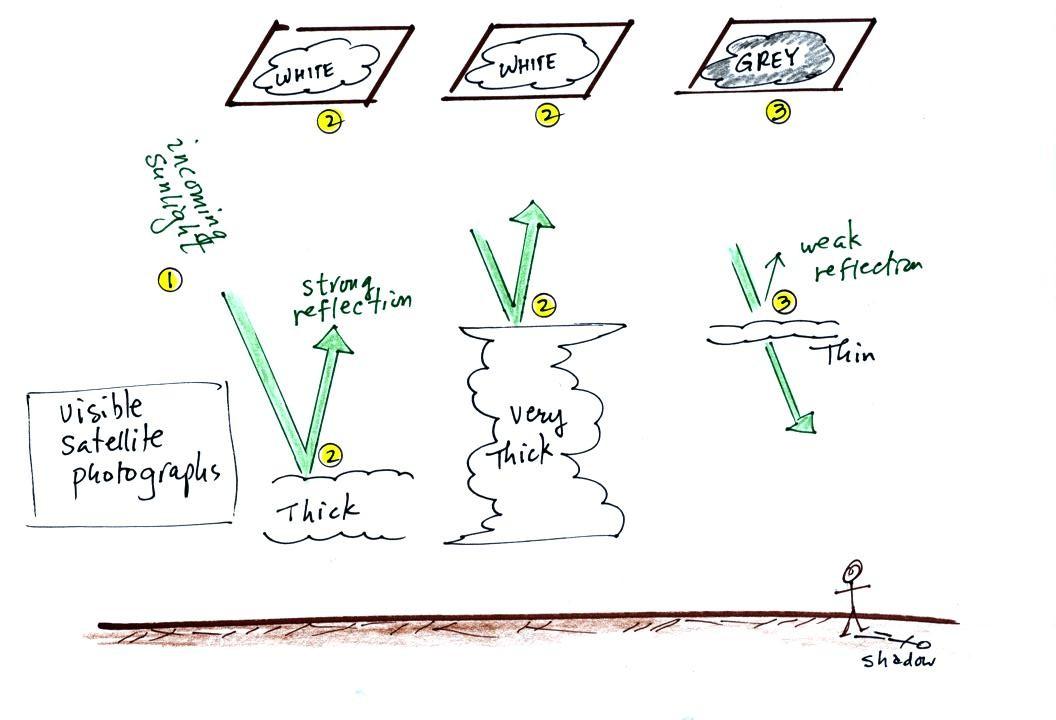

1. A visible satellite photograph photographs sunlight that

is reflected by clouds. It shows what you would see if you

were out in space looking down at the earth. You won't see

clouds on a visible satellite photograph at night.

2. Thick clouds are good reflectors and appear white. The

low altitude layer cloud and the thunderstorm would both appear

white on this photograph and would be difficult to distinguish.

3. Thinner clouds don't reflect as much light and appear

grey.

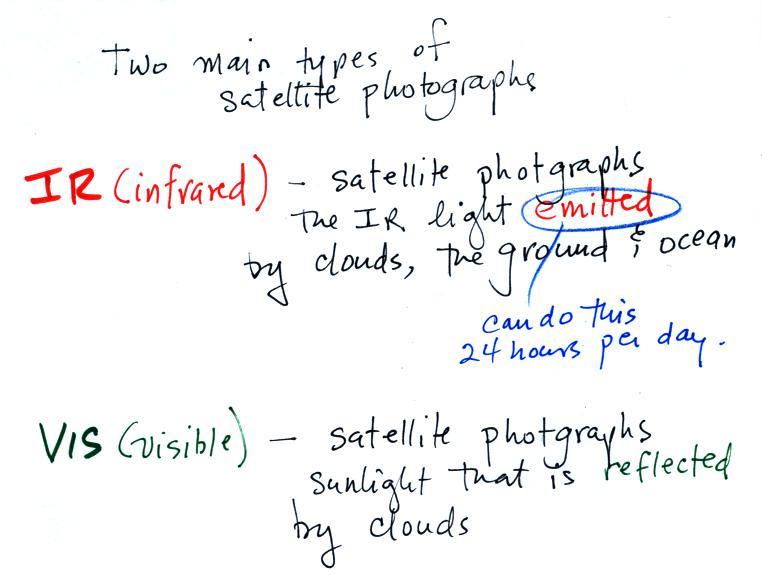

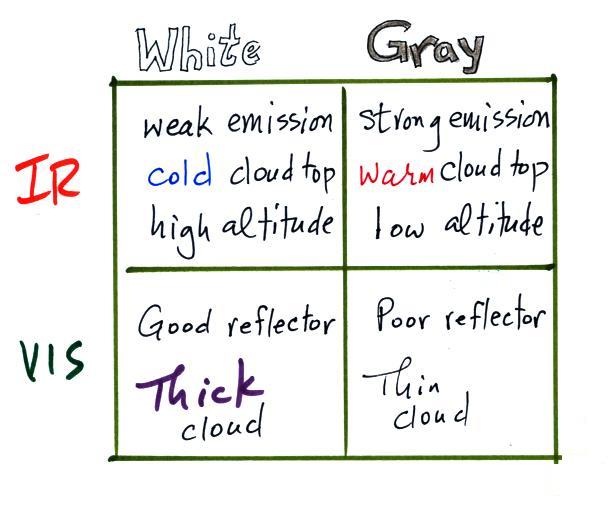

Here's a summary

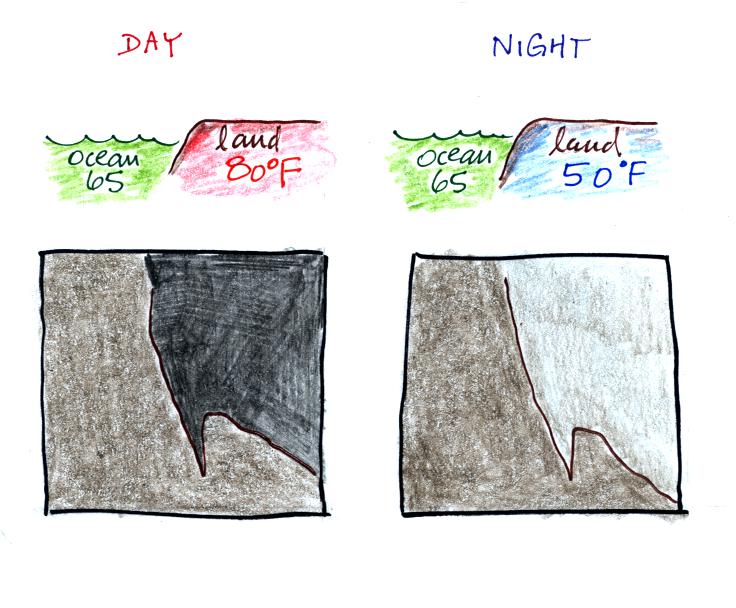

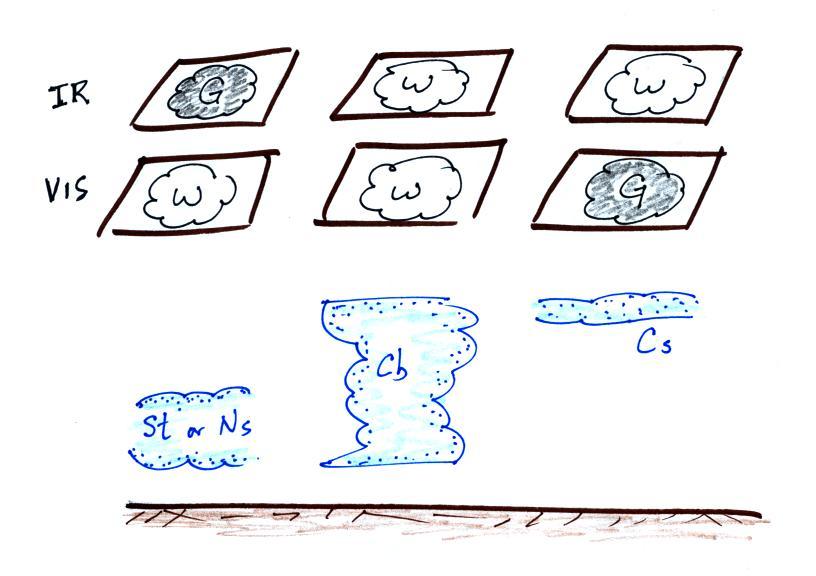

The figure below shows how if you

combine both visible and IR photographs you can begin to

distinguish between different types of clouds.